More On China's 'Missing Commodity' Scandal: Fallout Spreads As Banks Get Involved

Tyler Durden

While we have warned about the problem with near-infinitely rehypothecated physical/funding commodities/metals, be they gold [10]or copper [11], many times in the past [12], and most recently here [13], it was only yesterday that China finally admitted it has a major problem involving not just the commodities participating in funding deals - in this case copper and aluminum - but specifically their infinite rehypothecation, which usually results in the actual underlying metal mysteriously "disappearing", as in it never was there to begin with.

And disappearing commodities is exactly what we reported yesterday [14] the third largest Chinese port of Qingdao is being investigated for after a source at a local warehouse said that "it appears there is a discrepancy in metal that should be there and metal that is actually there... We hear the discrepancy is 80,000 tonnes of aluminium and 20,000 tonnes of copper, but we hear that the volumes will actually be higher. It's either missing or it was never there - there have been triple issuing of documentation."

This has resulted in a prompt and acute selloff of copper and other commodities as we further documents, but the problems may only now be starting and the banks, those which stand to lose the most if their "collateral" is uncovered to have never existed, are finally getting involved. As Reuters reports, worries over a probe into commodity stockpile financing at China's Qingdao port appeared to deepen on Wednesday as Standard Bank Group and a part-owned unit of Louis Dreyfus Corp warned of potential losses and copper prices fell further."

Responding to queries about the probe at Qingdao, which has not been officially confirmed, South Africa-based Standard Bank said it was "working with local authorities" to investigate potential irregularities at China's third-largest port, a major source for metal and iron ore imports.

"Standard Bank Group is not yet in a position to quantify any potential loss arising from these circumstances," the bank, whose Standard Bank Plc subsidiary conducts commodities trading, said in a statement.

Standard Bank is not the only one that may suffer major losses should the disappearance of rehypothecated collateral be confirmed:

Singapore-based logistics provider GKE Corporation Ltd warned shareholders that it was "assessing the potential impact" of the investigation on its GKE Metal Logistics Pte Ltd unit, a joint-venture 51 percent owned by global commodities merchant Louis Dreyfus.

While we expect many other banks to step up, for now these two are the first companies to publicly discuss the issue since the inquiry came to light on Monday, when Reuters reported the port in northeastern China had halted shipments of copper and aluminum as it launched an investigation into metal stockpiles used for collateral on loans.

To be sure Chinese authorities are in a bind: while they can't ignore the problem, a very aggressive investigation into the disappearance of collateral may result in a collapse of the entire rehypothecated house of cards, and they know it: according to Reuters, authorities at the port in northeast China have not officially confirmed an investigation, and have said exports and operations are running normally.

But earlier on Wednesday, Xinhua news agency reported that the port had said it was investigating whether iron ore warehouse receipts were fraudulently used multiple times to raise finance by different banks.

And while we have been warning about this problem for years, only now - when there is a documented case of alleged fraud - are the players finally starting to panic:

According to traders and warehousing sources, port authorities at Qingdao's Dagang wharfs have been examining whether there had been multiple issuing of receipts for single cargoes of metal tied to a trading company and linked companies.

The tumult has revived concerns that first surfaced in March, when China's first domestic bond default fuelled fears of further financing woes and triggered one of copper's steepest drops in years, with prices tumbling 8 percent in three days.

The immediate impact on pricing is clear, and just as we warned in March: lower.

"I think it's (copper) got more downside to go," said analyst Vivienne Lloyd at Macquarie. "That (the probe) will have the effect of making the banks extremely cautious about to whom they will issue letters of credit."

So while we are gratified that yet another event we have warned about has come to pass, what happens next is unclear.

Recall what we said in March, when we looked at the possible aftermath of a wholesale unwind of commodity funding deals:

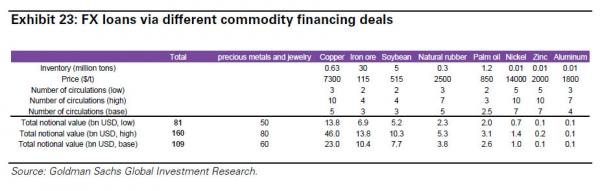

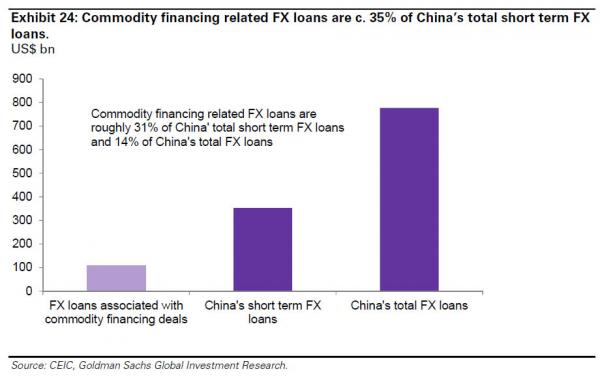

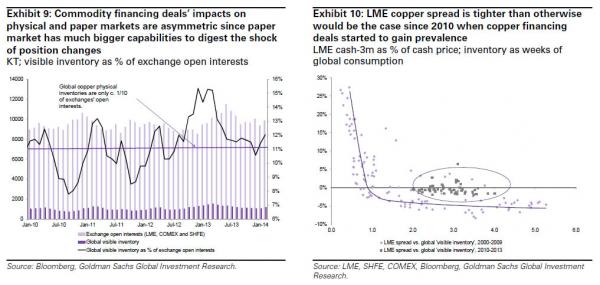

From a commodity market perspective, financing deals create excess physical demand and tighten the physical markets, using part of the profits from the CNY/USD interest rate differential to pay to hold the physical commodity. While commodity financing deals are usually neutral in terms of their commodity position owing to an offsetting commodity futures hedge, the impact of the purchasing of the physical commodity on the physical market is likely to be larger than the impact of the selling of the commodity futures on the futures market. This reflects the fact that physical inventory is much smaller than the open interest in the futures market. As well as placing upward pressure on the physical price, Chinese commodity financing deals ‘tighten’ the spread between the physical commodity price and the futures price.

... an unwind of Chinese commodity financing deals would likely result in an increase in availability of physical inventory (physical selling), and an increase in futures buying (buying back the hedge) – thereby resulting in a lower physical price than futures price, as well as resulting in a lower overall price curve (or full carry)." In other words, it would send the price of the underlying commodity lower.

Indeed as an unknown number of deals have begun unwinding, lower commodity prices is precisely what we have seen, just as predicted. But like in March, there is a footnote, one which pertains to a specific subject of Chinese funding deals: namely those which use gold, which as we showed before...

... is the metal most widely used in terms of notional to provide "metallic" funding.

We agree that this may indeed be the case for "simple" commodities like copper and iron ore, however when it comes to gold, we disagree, for the simple reason that it was in 2013, the year when Chinese physical buying hit an all time record, be it for CCFD purposes as suggested here, or otherwise, the price of gold tumbled by some 30%! In other words, it is beyond a doubt that the year in which gold-backed funding deals rose to an all time high, gold tumbled. To be sure this was not due to the surge in demand for Chinese (and global) physical. If anything, it was due to the "hedged" gold selling by China in the "paper", futures market.

And here we see precisely the power of the paper market, where it is not only China which was selling specifically to keep the price of the physical gold it was buying with reckless abandon flat or declining, but also central and commercial bank manipulation, which from a "conspiracy theory" is now an admitted fact by the highest echelons of the statist regime. and not to mention market regulators themselves [16].

Which answers question two: we now know that of all speculated entities who may have been selling paper gold (since one can and does create naked short positions out of thin air), it was likely none other than China which was most responsible for the tumble in price in gold in 2013 - a year in which it, and its billionaire citizens, also bought a record amount of physical gold (much of its for personal use of course - just check out those overflowing private gold vaults in Shanghai [17].

* * *

This brings us to the speculative conclusion of this article: when we previously contemplated what the end of funding deals (which the PBOC and the China Politburo seems rather set on) may mean for the price of other commodities, we agreed with Goldman that it would be certainly negative. And yet in the case of gold, it just may be that even if China were to dump its physical to some willing 3rd party buyer, its inevitable cover of futures "hedges", i.e. buying gold in the paper market, may not only offset the physical selling, but send the price of gold back to levels seen at the end of 2012 when gold CCFDs really took off in earnest.

In other words, from a purely mechanistical standpoint, the unwind of China's shadow banking system, while negative for all non-precious metals-based commodities, may be just the gift that all those patient gold (and silver) investors have been waiting for. This of course, excludes the impact of what the bursting of the Chinese credit bubble would do to faith in the globalized, debt-driven status quo. Add that into the picture, and into the future demand for gold, and suddenly things get really exciting.

So far it is unknown just what happens next: when it comes to copper and certainly gold, there has been a substantial downswing in prices. How much of that is attributed to CFDs unwinding is unclear. But the bigger question, and not just for gold prices, but for the Chinese economy is if indeed the funding deal house of cards is imploding, what happens to China's shadow banking system, which is extremely reliant on the billions in "rehypothecated" dollars emanating from non-existent metal collateral.

Because should the Qingdao port fiasco spread and be confirmed at all other venues that use commodities for funding purposes, then that may just be the straw that breaks the already weakened back of China's credit system. How the PBOC will respond to that may be just the variable that answers what happens to China's inflation, and thus to the price of the simple, unencumbered underlying physical metals in the coming weeks and days.

Stay tuned.

For those who want to learn more, please read "How China Imported A Record $70 Billion In Physical Gold Without Sending The Price Of Gold Soaring [13]"