Reflecting on Life’s Hopes and Dreams Through Renaissance Portraits

Lorraine Ferrier

‘Remember Me’ exhibition at the Rijks Museum, in Amsterdam

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

—Christina Rossetti, poet, from “Remember”

“Remember Me,” a fascinating exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijks Museum explores how over 100 Renaissance men and women were memorialized in paint. Through the portraits, we can see what our Renaissance cousins once held dear: their hopes, dreams, and achievements.

The paintings show how people wanted to be portrayed. They convey love, faith, family, beauty, ambition, authority, and knowledge.

- Leonardo to Matisse at The Met

- Popcorn and Inspiration: ‘Elizabeth’: A Queen as Divine as She Was Human

- Artist Uses Driftwood to Create ‘Gnarly’ Sculptures That Seem to Have a Life of Their Own

- Exceptional Art at Christie’s ‘Classic Week’

- Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’: Christ in the Epicenter of the Story

- More Dante Now, Please! (Part 3): Let Beauty Begin

Some 500 years have passed since these portraits were painted, but what’s astounding are the universal themes that resonate with our own aspirations today, affirming that traditional art truly and enduringly connects to our hearts.

The exhibition is a chance to reflect on great Renaissance art, from Northern artists such as Albrecht Dürer, Hans Memling, and Hans Holbein the Younger, to Italian artists, Titian, and Sofonisba Anguissola, among others. But more than that, the nine themes (such as “Admire Me,” “Cherish Me,” and “Pray for Me”) that exhibition curators Matthias Ubl and Sara van Dijk cover are an opportunity for us to reflect on our own legacy and impermanence. It’s a chance to ponder: When all is said and done and “the silent land” draws near, how do we want to be remembered?

For Beauty

The Rijks Museum chose “Portrait of a Young Woman” by Flemish artist Petrus Christus to promote its “Remember Me” exhibition. The portrait is a highlight of Flemish art and a highlight of the exhibition. This is the first time since 1994 that the Picture Gallery of the Berlin State Museums has loaned the portrait.

Christus’s unknown young lady certainly exudes something worth remembering: beauty. Renaissance men and women held the ancient belief that outer and inner beauty are intimately bound, explains Sara van Dijk in the exhibition catalog. Van Dijk uses Baldassare Castiglione’s 1528 “The Book of the Courtier” to illustrate this point: “A wicked soul rarely inhabits a beautiful body, and for that reason, outward beauty is a true sign of inner goodness.”

To convey beauty, portrait artists commonly emphasized purity, modesty, and chastity, highlighting the sitter’s virtue.

Christus painted the unknown lady in a three-quarter-length pose. Her porcelain skin and flushed pink cheeks allude to her ethereal beauty. She appears poised and humble, undoubtedly due to a righteous upbringing. She’s fashionable, wearing a blue Burgundian-style dress and a black stomacher (the decorative insert of a woman’s dress that covers her bodice).

Van Dijk notes that fashionable attire had a certain place in women’s portraits, but women were not to neglect their wifely and motherly duties because of vanity. “It would be ugly and distasteful for a nobleman’s wife to appear publicly wearing garments suitable for a duchess or a queen,” wrote Renaissance humanist and philosopher Alessandro Piccolomini.

For Love

Van Dijk explains that in medieval times, devotion to God was of the utmost importance. Devout Christians lived as celibates, dedicating their lives to God. But celibacy was not an option for all. The sacred bonds of marriage offered redemption from the deadly sin of lust.

She describes matrimony as a sacrament bestowed by Christ “as a symbol of his relationship with the Church. He was the incarnation of the Word of God, and this was symbolized by the physical and spiritual union between a man and a woman. Thus, Christ’s relationship with his Church was mirrored in the harmonious relationship between husband and wife.”

Betrothal and wedding portraits reflected what Renaissance men and women believed to be important attributes for a successful marriage and a fruitful family life. Portraits were filled with symbols of love, purity, chastity, and fertility.

An endearing marriage portrait is “Portrait of Marsilio Cassotti and his Wife Faustina” by Italian artist Lorenzo Lotto. The bride’s father commissioned the piece. In the portrait, Cupid presides over the couple as Cassotti takes his soon-to-be wife’s left hand to place the wedding ring on her finger. Van Dijk notes that in Northern Italy the wedding ring was placed on the right ring finger, not as portrayed in Lotto’s portrait. Perhaps the painter was suggesting a very old tradition: In ancient Rome, the wedding ring would be worn on the left hand, as Romans believed that the left ring finger connected, via an artery, directly to the heart.

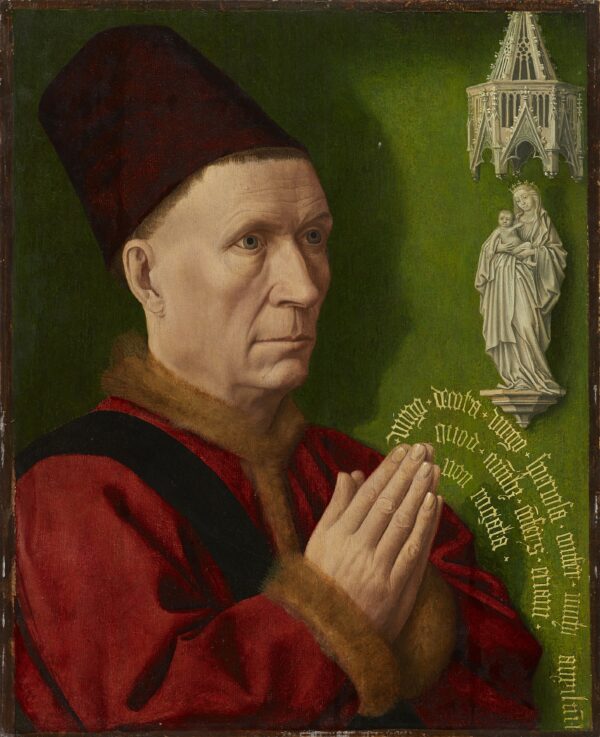

For Faith

Prayer was often depicted in devotional portraits. For Christians, the act of prayer offered a direct link to their salvation, paving their path to heaven.

Christians kept devotional paintings as daily prompts, reminding them of their Christian vows. These private portraits were often small portable pendants, diptychs (paintings made of two panels that folded onto each other), or triptychs (similar to a diptych but made of three panels, with the central panel often depicting a religious figure). These were designed to be easily transported or displayed in monastery cells to aid meditation.

A diptych in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Dijon, France, of a married couple—titled “Portraits of a Praying Man and Woman”—was created in Burgundy, France, around 1470 by an unknown artist. The couple, painted on separate panels, are both venerating sacred sculptures. The husband solemnly prays to the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, and his wife humbly offers her prayers to John the Evangelist. From the husband’s hands flows a Latin inscription, as if affirming his silent prayers.

“These devotional portraits were probably also intended to keep the prayer going symbolically throughout eternity: The paintings, as it were, took over the prayer function when the sitters were busy with worldly occupations or had died,” writes Matthias Ubl in the exhibition catalog.

Other devotional portraits were generously peppered with sacred symbols, some overtly so, such as the rosary. Other symbols, although known to the Renaissance contemporaries, may need further explanation today. Prayer nuts, for instance, are often featured in the paintings. These were boxwood nuts that opened into two halves and contained sacred carvings, often depicting the Passion, which acted as a meditation tool.

Artists also depicted pilgrims’ portraits, as seen in Dutch artist Jan van Scorel’s painting “Twelve Members of the Haarlem Brotherhood of Jerusalem Pilgrims.” The pilgrims’ destination, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, is painted in the top-left corner of the painting. Everything in the portrait reminds the pilgrims of their divine vows. Each brother is in chronological order according to when he made his pilgrimage. Each pilgrim holds one or two palm fronds, with each frond indicating a completed pilgrimage. Papers along the bottom of the painting urge the brothers to pray for the deceased pilgrims, to help them in the afterlife. The artist placed his likeness in the painting, as he was also a pilgrim. Van Scorel stands above the detached piece of paper. Ubl says that the detached paper represents the impermanence of life.

Artists depicted the transience of life in “vanitas” portraits. “The Word of God is everlasting, all else is temporary” states a Latin proverb on one portrait. Commonly, symbols of impermanence such as carnations, hourglasses, soap bubbles, and the more macabre motifs such as skulls and even rotting corpses are featured in these portraits.

For Artistry

Early self-portraits were made to honor God and show the beauty of His creations, Ubl says. Later, self-portraits deviated from those sacred intentions. Self-portraits became promotional tools for artists to display their talent and ambition. Ubl notes that the shifting emphasis in portraiture from God to the individual directly correlated with the elevation of the medieval craftsman to artist.

Artists had inserted their self-portraits into their work prior to the 16th century, but now artists painted autonomous self-portraits mainly to allude to their craft. Ubl notes that those portraits that didn’t hint at the artists’ occupation were painted by court painters who had no need to promote themselves.

Dutch artist Maarten van Heemskerck’s “Self-Portrait With the Colosseum” is a fascinating self-promotional painting. At first glance, the artist appears in front of the Colosseum, but he actually depicted himself in front of a painting of the ancient monument. In the far-right corner, we can see van Heemskerck at his easel, copying the amphitheater as part of his Grand Tour art education. Through this painting, he is telling his prospective patrons that he’s not only skilled, but that he is also learned. He has been on his Grand Tour and copied the best examples of art: those of ancient Rome.

Like van Heemskerck, Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola showed her prowess in paint. She created many self-portraits, a couple of which are in the exhibition. In one, she is at her easel painting the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. Religious history paintings, such as the one on her easel, were esteemed as the highest genre of painting.

Another of her paintings in the exhibition, painted just a year after her self-portrait as an artist, is her delightful and well-known family portrait “The Chess Game.” In this painting, Anguissola looks out at the viewer while her sister on the right tries to get her attention, as if urging her to make her next chess move. Anguissola’s other sister, in the center, cheerily looks over to her sister on the right. It’s a joyous family scene. A few years after those paintings, in the winter of 1559–1560, Anguissola became a court painter and a lady-in-waiting at the Spanish court, teaching art to Philip III’s third wife.

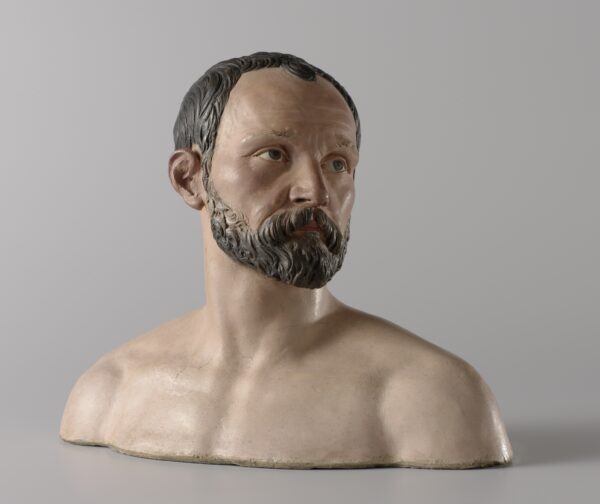

One self-portrait summarizes the exhibition well. Dutch artist Johan Gregor van der Schardt’s self-portrait in white terracotta with polychrome, stripped of clothes and any other indication of time, espouses the timelessness of the different ways people want to be remembered. Take away any hint of the period in which these portraits were created and what remains are people representing the enduring, traditional values of our shared humanity.

The exhibition, “Remember Me” runs until Jan. 16, 2022, at the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam. To find out more, visit Rijksmuseum.nl

The exhibition book, “Remember Me: Renaissance Portraits,” can be purchased online from the museum shop; visit RijksmuseumShop.nl

https://www.theepochtimes.com/reflecting-on-lifes-hopes-and-dreams-through-renaissance-portraits_4063834.html