THE LAND FOR THE (CHOSEN) RACKET

C.H. DOUGLAS

THE “LAND FOR THE (CHOSEN) PEOPLE” RACKET - first appeared serially in THE SOCIAL CREDITER between December 1942 and March 1943.

(SCROLL DOWN)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

(The foregoing quotation is alleged by the People to whom it is attributed, to be a “forgery,” so we will say that it is one of Grimm's Fairy Tales.)

I suppose that there never was a time when so much nonsense was talked by so many people on so many subjects, as the present. Sober judgement was once the object of respectful attention; but nowadays none is so poor as to do it reverence. The very foundations of considered opinion appear to be undermined; words, in our new “wonderland,” mean what we want them to mean, and are used, not so much to conceal our thought as to advertise our determination to dispense with it.

High up on the list of matters on which almost everyone feels competent to give a firm, not to say strident, opinion, noticeably at a time like the present, which one would have imagined to be inopportune, is the subject of “the land.” No experience is necessary; in fact, it is a serious handicap; it cramps your style. From the Archbishop of Canterbury, who is primarily a schoolmaster, through Mr. R.R. Stokes, M.P. who is a machinery manufacturer, to the shadowy backers of the Commonwealth League, all agree in their line of criticism—more laws “ought” to be passed about the land, and it “ought” to “belong” to the “people.”

There are many concrete facts the consideration of which is essential to an appreciation of the threat, not to that system (whose assets are being bought up with paper money at scrap prices), but to the individual Briton, which its disappearance involves. If the delusive word “ownership” can be forgotten for a moment, it will be easy to realise that it was a highly articulated system of administration, developed by trial and error over a long period.

To the agitator (though not to his hidden paymaster) “land” is homogeneous; an acre is an acre whether it is on the slag heaps of Widnes or the High-farming land of the Lothians. Agitation is moulded to justify “office-management” in place of personal responsibility.

One of the first considerations of the old system was to maintain, in the real, not the financial sense, the capital value of the land, and to do this required extraordinarily detailed knowledge of local conditions and custom. The desperate condition of much English arable, which has been “farmed-out” by tenant farmers not properly supervised, and having little anxiety as to their ability to get another of the hundreds of farms on offer, is the direct result of the sabotage of this administrative system.

But it is easy, more particularly in war-time, to look upon “the land” as though it were almost entirely an agricultural and production problem, which is the usual misdirection of emphasis fostered by international finance. It is primarily, but not principally an agricultural problem. It is, I think, a problem which can easily be misapprehended, unless it is considered in intimate relation with the character of the population, as well as its numerical magnitude. For instance, the last pursuit in which the land agitator wishes to engage, is farming, nor do farmers do much agitating.

There are many very curious circumstances surrounding the question of population statistics, and population habits, in Great Britain. William Cobbett was aware of them. They have become still more curious in the last hundred years, as anyone who will take the trouble to consider the figures available in Whitaker's Almanac can see for himself.

II

I do not think that it can be reiterated too often, at this time, that except as a purely legal fiction, the common ownership of the soil by 45,000,000 individuals is not a subject for debate—it is a factual impossibility. In the sense in which it is understood by the ordinary man, ownership means control. Forty-five million people never yet controlled anything. If they can't control the Post Office, or the Army, Navy, or Air Force, and can't even control their individual and collective involvement in a war they didn't want, and don't understand, how can they control sixty million acres varying from limestone rock to water meadows?

So far as the produce of the land is concerned, that is available to anyone who has the money. Has anyone suggested that “the People” should have the produce of the money-making machine?

Conversely, do the agitators for common ownership yearn to pay the taxes now borne by land? Ask most of the farmers who bought their farms during and immediately after the 1914-1918 war period how they like their bargain, from the business point of view. If the older conditions of estate management were so unfair to the tenant, how was it that farmers' sons had to wait years before they could get a vacant farm, and had to be well known to be thoroughly competent farmers, or they would never get one; while nowadays there are hundreds of once-famous farms going begging, and every day good farmers are throwing in their farms in disgust at the ever rising tide of interference without responsibility?

If the farmers are worse off, the “owners” are ruined and dispossessed, “the people” are getting worse produce at higher prices, and the land itself is impoverished and “farmed out,” quis beneficit?—who is better off?

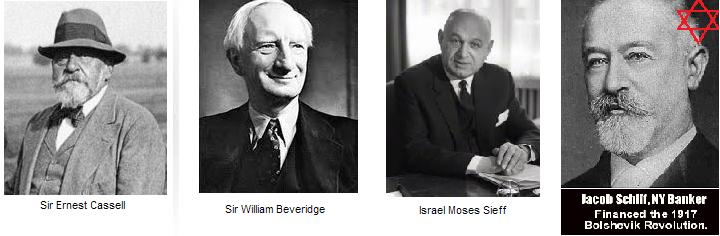

It will be remembered that (a) Lord Haldane said that Germany was his spiritual home, and (b) that Sir Ernest Cassel was the alter ego of Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn, Loeb, and Company.

Now there is no room for discussion as to what has caused the disastrous state of British land and everyone connected with it. That cause is grinding and punitive taxation.

And this taxation has for the most part been concocted either directly or indirectly by the London School of Economics—a good deal of it by Sir William Beveridge who we are to entrust with the building of our New World, “half way to Moscow,” as he puts it so engagingly. An understanding of the main principles of current taxation is indispensable to anyone who claims to hold views on the future of the soil. In the first place, it is necessary to recognise three classifications of the surface— agricultural, industrial, and residential.

The question of minerals underground is closely interwoven with the surface classification, but may be left for subsequent consideration. It is a question which, if possible, is less understood by the average land agitator than that of the surface.

Now, land taxes begin with a series of recurrent capital levies at each inheritance, thinly disguised under the names of Legacy Duty, Estate Duty, and so forth. It must be borne in mind that (in spite of nearly

unworkable alternatives of recent date) these have to be paid in money, and land does not grow money. Generally, this money is borrowed on mortgage or otherwise. These “Duties” may range from 10 per cent. in the case of very small properties, to sixty or seventy per cent. in the case of very large ones.

In effect, these taxes are confiscatory, consequently whatever is the state of the land at the present time, that state is the result of a change of effective “ownership.”

Subsequently to the Capital levies paid by the legatee, but not by anyone purchasing the land, Income tax at the current rate (now 10/- in the £) is paid on the ownership of the land, not on the return it makes, but on an arbitrary assessment which goes up if the land is improved. This assessment is generally made by the local rating authority who levy their own distinct taxes, called Rates, on it; and these go up if the land is improved. But if the owner also occupies “his own” property, he pays Schedule B as well as Schedule A and Rates, also at the current rate. (The foregoing statements are subject to certain modifications in respect of Scotland, and to the vagaries of Derating Acts.) In effect, the owner-occupier of his “own” property pays, at the present time, more in rates and taxes than he would have paid in rates, taxes and rent, sixty years ago, as a tenant. It is a sound legal, as well as common-sense axiom, that a man must be presumed to have intended the logical consequences of his actions. The logical consequences of the taxation just roughly summarised can be seen to be what they have in fact been. They have made the use of land for agriculture only precariously possible by treating as soil income what is in fact soil capital; thus fostering overseas imports of easily grown food.They have made the “ownership” of land, as an administrative profession, impossible by imposing what is in fact an intolerable nationalised rent.

A short survey of the bearing on all this of what were called “Mineral Rights” will enable us to pass on to a consideration of why once-Great Britain is unique in its taxation, the objective of it, and who benefits. That will clear the ground for the possibilities of a reasonably sane system.

Valuable minerals are not widespread, even in these islands which were unusually rich in them until we gave most of them away. The consequences of this were two fold; mineral owners were few in number, and so politically weak; and the largest of them was the Ecclesiastical Commissioners who paid no Estate Duties; and owing to the immense quantity of mineral obtainable from a small area, individual owners gave the illusion of being “rich,” more especially as most of them were abysmally ignorant of the idea that they were living on capital in the most literal and wasteful way it is possible to conceive.

Now, it is of course possible to reduce any discussion about the rules, conventions, and practices either of society, business, or even a game, to a mere brawl, by introducing the word “ought.” While I am not able to see, myself, just exactly what “the People” and more particularly the Chosen People, did to produce the coal deposits under these islands, these comments have nothing whatever to do with the word “ought.” It is not merely possible, it is easy, to raise the standard of living of the legitimate population of these islands to a point considerably exceeding that of any Socialist State; but that has nothing to do with “the minerals ought to belong to the Nation,” or the results of the expropriation of mineral owners, which, to make the matter clear at once, have been to mortgage them to the international Jew, via the various forms of Debt.

As I have mentioned elsewhere, it was freely stated in Washington in 1919 that a bribe of £10,000 was paid to a certain witness before one of the well-known commissions on the Coal Industry to recommend the nationalisation of coal. I feel sure the £10,000 will appear in the bill, if not recognisably.

Coal royalties while obviously and indisputably payments in respect of capital, and taxed on that basis in Death Duties, were again taxed as income. They were again taxed by coyly worded bribes to further attack, such as Mineral Rights Duty, Miners' Welfare Levy, etc. At which point, we come to the interlocking with surface “ownership,” and it may be becoming clear that whoever “owns” the land, the Big Idea in regard to it is that it shall be rented from the World Debt Holders.

IV

The “owner” of minerals had no choice whether they should or should not be worked. He was obliged to grant a lease to a Colliery, on demand and at practically its price, but the Colliery had complete freedom as to whether or not it would work them. It is true that in many cases the Lease contained a “minimum rent” clause, usually about £1 per acre, but this so-called “rent” was afterwards deducted from the royalties together with all bad coal, “faults,” etc. In effect, for about twopence per ton, the colliery got control of all the coal without buying the surface and with the whole of the political responsibility and abuse directed against the “owner.”

Now let us see what happens to the surface. In the first place, it becomes for a lengthy period unsaleable for building purposes, because of the danger of settlement, and this unsaleability causes a money loss probably greater than the total sums received, net, for the royalties. In the second

place, miners, very good fellows as they are, are not regarded with enthusiasm by farmers.

They are inveterate trespassers and poachers; destroy fences, leave open gates, and produce an easily recognisable “ragged” air to the countryside which is accentuated by the “planned” neatness of many modern colliery villages. The sulphur smoke from the pit chimneys hurts the crops. And of course, by the almost inevitable destruction of the amenities of the district, its general residential value becomes restricted to those connected with the working of minerals.

Notice that the “owner” has nothing whatever to do with this state of affairs. He merely pays the taxes, is pilloried by the miner as battening on the virtuous worker “who produces all wealth” and hasn't sufficient experience to realise that the “wealth” he produces goes mostly, as an American manufacturer recently put it, to provide a quart of milk a day for Hottentots. That is to say, it is exported practically free, and goes to swell the thousands of millions of pounds of capital which have been lost in the last fifty years.

While fundamentally, of course, the financial aspect of the matter ceases to be of importance with the sabotage of private “ownership,” it may be noted in passing that International Bond holding is doomed on the day that “ownership” passes to the State and the State itself would hardly survive. The rent and maintenance charges which would have to be collected to pay the Bondholders, of whom individual War Loan holders form a small part, would then be so impossible that, the private “owner” having disappeared, the real malefactors would be easily recognisable— to quote that professional maker of phrases, Lord Baldwin, during the past half century, the Government, whatever we may mean by that, has “realised the ambition of the harlot throughout the ages—power without responsibility.”

There is no room at all for difference of opinion as to the relative excellence of management by private ownership or by the bureaucracy by which it is being replaced. Leaving out of comparison such outstanding instances as the Buccleuch or Stanley Estates, there are still hundreds of small properties in which ownership is maintained by extraneous funds, which are immeasurably superior to the properties of Government Departments disposing of practically unlimited funds.

Was there then, no room for complaint about the system? I think that there was. And, for the moment, there is every evidence that, so far from its defects being rectified by State Management, they will be greatly magnified.

During the past few months every considerable newspaper has printed, in its correspondence columns, a large selection of letters on the profit motive, and I do not think that it is unfair to say that this correspondence has in the main fostered two very significant ideas. The first of these is that the profit motive is both bad and is confined to a restricted class from whom all the evils of society proceed. And the second of these is that the profit motive is either another name for a system of private property, or if not that, is inseparable from it. There is not, I think, even a substratum of truth in either of these ideas. They are an evident example of systematic perversion applied to popular psychology.

One of the riddles current in our nursery days was “Why does a hen walk across the road?” to which a perfectly correct answer might have been returned “From the profit motive.”

The moment that any human being performs a single action for any reason other than that provided by the profit motive, he is a certifiable lunatic. It is simply a question of what is, in the mind of the individual, profitable to him, taking all the factors and consequences of the action into consideration. The Trades Union Movement is the biggest example of an organisation run purely for profit, for nothing else but profit, making nothing whatever and with sublime disregard for the profit of anyone not belonging to it, which this country can show. During the present war, the economic profit of every class of the community has been sacrificed to the over-riding claims of the Trades Unions, and it is an essential aspect of this situation that Trades Unionism is normally more concerned with internationalism, at least overtly, than any other allegedly national institution. And the declared policy of Trades Unionism is Socialism, which is another word for monopoly in land, labour, and capital.

One of the remarkable features of the confiscatory taxation on land and private property of every description, is the tenacity with which individuals have held on to it in the face of the heaviest financial loss. To say that, in the main, for the past seventy-five years, landowners have been actuated by the determination to make a financial profit is simply another way of saying that landowners are all fools.

It may reasonably be asked why, if only lunatics act to their own disadvantage, anyone should want to “own” land. The answer to that is probably the key to the situation. A comparatively small number of individuals do want to own land as distinguished from an income from land, but those people can do things for and to the land which no bureaucracy can ever hope to do. And those people will not do it, if they are interfered with. Hundreds of farmers, and remember farming is only one aspect of the question, are throwing in their farms although, for the first time since the last phase of the international war, they are “making money.”

What, then, was the genuine defect of the big estate system? Remember, the ruined country side is definitely the result of financial attack largely from alien sources. I think that the answer is evident to anyone who was familiar with the large estate. It was not primarily as a system of administering the land that it failed. It was that it gave too much power over the general lives of the individuals who worked on it.

Now this defect—and it was a serious defect—was not peculiar to landowning, and it is not less, but rather greater, in such large industrial settlements as those of the Ford interests in the United States, and the Port Sunlight “model villages” in this country.

Many of the American industrial organisations arrogate to themselves a right of supervision over the private lives and morals of their employees far exceeding that which would have been exercised by a British landowner at any time, or tolerated by their tenants, and this is accompanied by a close knit organisation for card-indexing every applicant for employment, and penalising by unemployment and starvation anyone daring to rebel against the rules. But we do not hear of organised attack on these things.

Paradoxically enough, the very security of tenure enjoyed by tenants on large estates tended to increase their dependence on the landlord. Many of them were rooted in the soil to at least as great an extent as the titular owner of it. They were specialists and they instinctively recognised that transplanting was a serious, perhaps a fatal thing to them. When the landlord was equally stable in his tenure, the despotism was not so much felt since tradition limited it. But when estates began to change hands by purchase, in many cases coming into the possession of men with no knowledge of, or feeling for, the land, but an exaggerated idea of their own importance, the despotism tended to change from what was in the main, a benevolent, while rather mediaeval overlordship, to an irrational tyranny. To take a simple instance, fox-hunting. I need, perhaps, hardly say that the point I should like to make has nothing to do with the ethics, or otherwise, of fox-hunting as a sport. The Meet of Foxhounds of John Peel's era was a neighbourly affair, comprising two or three squires and their families, and perhaps twice that number of yeoman and tenant farmers. All of them knew every inch of the land, rode carefully over it, and did negligible damage which was jointly repaired. But as the City men began to take to hunting by the process of sending a subscription to packs which were too expensive to be kept by one man, the whole atmosphere changed. Hundreds of strangers mounted on horses brought in by train, ridden by people who knew little of the country, and cared less, galloped over the land leaving a trail of damage which was a serious nuisance, to put it no higher, to the tenant farmer, who was no longer welcomed, or in fact able to hunt himself in the expensive company of the larger Hunt. But protest was not healthy—it didn't pay.

During the last hundred years, the position of Agent, or, in Scotland, Factor, has become of increasing importance in considering the administration of land. The Agent represents a definite step in the transition from personal to “office management.” In considering it, it is important not to overlook the fact, that, particularly in Scotland, there are certain families, exclusively connected by long association with large landowners, who are just as hereditary as the owner. There is one family, whose name will be familiar to any Scottish farmer; whose estate management is by common consent as near perfection as an imperfect world will permit.

But it should be particularly noted that the hereditary, personal touch is merely split into decision on main questions of policy, which are reserved for the attention of the proprietor, and routine administration, which is the field of the Factor. It is poles apart from Bureaucracy.

VI

Management by a Firm of Estate Agents acting for several owners is quite another, and begins to approximate to bureaucratic management—so much so, that in fact it is not infrequently a branch of the business of country solicitors. Where, as in perhaps the majority of cases in Scotland, the so-called proprietor is hopelessly in debt to a bank or an insurance company, the Agent is in fact concerned neither with the interests of the land, the proprietor, nor the tenants, except in so far as they maintain the security behind the debts, and ensure the due collection of the interest.

He is frequently resident in the bank itself. To apply the term “private ownership and management” to this state of affairs, is nonsense. The essential point to grasp is, I think, this. The possession of legal title to land, and the drawing of rents from it is an entirely separate question from the merits or other wise of the control and administration of land by genuine private ownership, which does not necessarily involve residence but does imply knowledge and initiative.

At bottom, there is little doubt that there are two irreconcilable ideas in conflict.

The first of these is that the world in which we live is an organism and that men and animals have intricate relationships with the earth—not amorphous but specific and infinitely varied, which can only be disregarded at the peril both of men and the earth they live on. I do not mean in the least by this that a universal back to the land movement is either

necessary or even desirable, but I do think that the idea that the earth is merely something to be exploited and “lived on” is quite fatal.

It is this unresolved antithesis which makes the Planners so dangerous. No one with ordinary intelligence would contend that, when you are quite sure that you want to go from London to Leeds, you should not “plan” your journey, within certain well defined limits. But if all you know is that you want to go from London to a health resort, you are very foolish if you allow the Leeds Association of Boarding House Keepers to say that Leeds is the only health resort, and anyway, they are going to take off all the trains to anywhere else.

Before the land question is capable of any “solution” which will not make things worse, if possible, than they have been made by the activities of the wreckers, certain sedulously propagated theories simply must be cleared out of the way. The first, of course, is that it is the business of the Government to “put the people to work.” Perhaps the shortest way in which to deal with this is to say that, if the facts of the case require that an individual must work before it is possible for him to obtain those things of which he has the need or desire, then he shall in no case be prevented from working by artificial restrictions. But if, without injury to others, he can be provided with these things without working, the fact that he has not worked for them shall be recognised as a matter of no consequence whatever.

Now I consider that this question is so important that I should regard as perhaps the most hopeful event of the last few years the obvious breakdown of what is known as the Means Test. The issue of purchasing power to a limited minimum, tout court, immediately frees nearly every social question, including the land question, from the devastating misdirection involved in claiming “the right to work,” not because you want to work, but because you must be paid. At one sweep, it clears away hundreds of thousands of people who would not know what to do with land if they really controlled it. And I think that it enables us to see dimly that the curious atmosphere of scarcity, with which, in common with everything else, the land question has been surrounded, is, or could be a delusion also. It might be useful to recall that Mr., now fittingly, Lord Keynes predicted that owing to the disappearance of Russian wheat from the European market, wheat would rise to £5 per quarter and would be wheat in Canada and the Argentine that it was burnt for fuel and the growers were financially ruined by the fall, to the lowest on record, of the price.

But we shall not get very far by the naive method of dividing the area of the land by the number of the population.

“A Servant when he Ruleth—”

If I were asked to specify the most disastrous feature with which the world in general, and this country in particular, is threatened, I should reply “The rule of the Organised Functional Expert—the engineer, the architect and the chemist, amongst others.” As I am an engineer and retain the most wholehearted affection for engineering, I may perhaps be credited with objectivity in this matter.

When a nation has declared war, it has finished with policy, because war is a function whether we consider it to be natural or a malignant disease. It is, par excellence, the rule of a function, its experts, and their organisations. Under cover of this obvious fact, a spate of other experts is being let loose on us, with their Reports—the Uthwatt Report, the Scott Report, the Cooper Report on Hydro-Electric Development in Scotland, the Report of the County and Municipal Engineers’ Institution, and so on. Every one of these Reports conflicts with the functional Rule of War, and each, without exception, deals with Land Policy without giving any indication that the very fact that their authors are reporting as experts automatically discredits them as politicians, using this word in the sense in which it ought to be, but generally is not, understood. It is curious, also, that the Henry Georgeites, the Land Taxers, are furiously active just now also.

Let us be specific. The Municipal and County Engineers' Report “assumes that the policy of high-speed motor roads with link to the Continent” will be adopted in Britain (not Great Britain). Yes? Who authorised that assumption? Not, by any chance, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders? The Report remarks, “Public control of land is essential, even though it may interfere with the full enjoyment of private ownership.” What the Municipal and County Engineers as an organisation mean by Public control of land is more and bigger staffs of Municipal and County Engineers to play about with the land to the detriment, as they boldly put it, of private, i.e., non-functional, enjoyment.

However this may be, I have never met a private individual unconnected with aluminium who did not regard this road, built at enormous public expense, as a first-class calamity.

VIII

“But, my dear fellow,” observes Mr. Pink-Geranium; O.B.E., (né Rosenblum) of Whitehall, “what has all that got to do with it? Don't you know that rabbits are destructive to crops? I have here a report (sponsored by a really international, my dear fellow, chemical combine, which makes cyanide for exterminating rabbits and human beings) which puts the matter beyond doubt.” To this the obvious reply is that all the rabbits in Christendom have not destroyed as much food in a century as Mr. Pink-Geranium and his London-School-of-Economics policies have destroyed in the last ten years, and that if these policies are to prevail, why not let the rabbits save the trouble of sowing, reaping, storing, and then burning the millions of bushels of wheat Mr. Pink-Geranium won't let anyone buy? To pretend that the rabbit eats only crops, and has no contra-account, is typical.

As an obvious consequence (even if no other factors were involved, which is far from being the case) there are fewer families to work even existing workable land. What is the argument, then? Are the deer on the high lands driving the population into the towns and even out of the country? Is there any evidence whatever (more especially since the spectacular failure of forced evacuation) that even if given free land, any considerable proportion of the urban population would, or could, work the high tops? If so, I have not heard of it. Can it be that the red-deer is the very symbol of freedom, and so, hateful to Mr. Pink-Geranium?

The heavy-handed, crude, mass methods of a Government Department are wholly unsuited to land administration. But they can, and do, sabotage humanised management.

It had been formed by an owner who was an acknowledged authority. His whole life's work and interest was bound up with his cattle. Every possible argument was brought to bear upon the Board of Agriculture, without effect. Every animal, sick or well, was slaughtered. The owner died of a broken heart a few days later.

interference with nature, if it is not to be catastrophic, must be inspired by something very different from the rigid formalism of a Government Department. The modern Government Department has its roots in the departmentalised pseudo-science of the Encyclopaedist fore-runners of the French Revolution and its lineal descendant, Russian Bolshevism.

“As regards private leases, at least of rural subjects (as is well known), tenants after a long fight obtained ‘compensation for improvements,’ but under these new proposals not only the new ‘Crown tenants' but even the about-to-be-converted feuars are to be shorn of that long-fought-for right. Worse still, the doctrine of the English Crown-lease is apparently to be applied—that the tenant is responsible for leaving the building in order, and will be held responsible for the cost of doing that (maybe thousands of pounds) to the State's satisfaction.

and when, it is discovered that waste, corruption, and disillusionment are rampant—well, that's just too bad, but we've done it now.

XIII

Considering first the purely agricultural aspect of the land question in the light of the assumption that “we must grow more food”—an assumption which I am inclined to believe has some basis in reality—the policy decides itself. Comparatively small agricultural holdings, of the order of one hundred acres, or so, are at least 30 per cent. more productive than mechanised collective farms. Incidentally, much more information ought to be available regarding Forestry Commission farms. It is, of course, important to distinguish productivity per acre, from financial profit per acre under an arbitrary financial and wage system. Accurately costed on orthodox (and in a technical sense, correct) costing system, I doubt very much whether any English farming made a legitimate money profit on sound and properly remunerated management. That is merely an argument for better financial methods, not for a different system of administration.

Now, it is convenient to refer to Groups as if they had a separate existence, but, if we are careful to allow for what may be called the Group Spirit, we make no mistake in looking for the men, the living forces, who activate it. And it may easily be true that we shall get more information as to the way they think, if we look for it in places where its expression is less conscious than in the Board Rooms of the Central Banks or the International Combines. For this reason let us consider the recent address to a mixed body of industrialists, bankers, and uplifters, by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Temple.

that the land question is unduly difficult. I should say that the essentials of the solution are: