Kennedy Unbound

Charles P. Pierce - Globe Staff

Sept. 9, 2009

(Jan. 5, 2003)

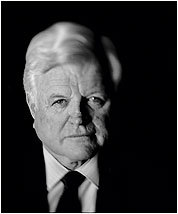

There's nothing to see out the windows. A dense mid autumn fog has swallowed the view of Boston Harbor from the 24th floor. So, instead, look at him. There's something to see there, framed in gray mist and rain, Edward M. Kennedy, 70 years old now and 40 years as senator and a politician and celebrity and all the rest of it. See how he's not gone all gut-fat but rather squashed, with that Irish hunch that makes the old ones look bowed and slowed, as though their lives collapse inward like stars, all the extraneous material consumed until there's nothing left but the invisible gravity of the core. See how his right hand quivers until he covers it with his left, a gentle movement that he camouflages by looking at his watch.

His conversation is still erratic, an AM radio stuck on scan, chopped to bits by strategic throat-clearing and by pauses that are long enough to be considered tactical. He's talking about how the Republicans in the House refused to fund fully an education initiative that he'd worked on with President George W. Bush and that Bush had signed with great fanfare early in his term. No Child Left Behind, it had been called. Kennedy had been so instrumental in developing the legislation that some of Bush's more conservative supporters had grumbled that the new president was being played like a tin piano by the Evil Genius of a thousand rightist fund-raising appeals.

Bush signed the bill anyway, and House Republicans walked away from funding most of it. Maybe the president knew they would. Maybe he didn't. Kennedy shrugs at the politics of it. They only came across with the money that made it easier for poor parents to be more directly involved in early childhood education.

That morning, Kennedy had visited a local facility where that part of the program had been implemented.

"It's an obvious factor," Kennedy says. "Children learn from their parents, and then they learn at school. It should be obvious that children will learn more if we can help the parents be involved. There was a lot of resistance to No Child Left Behind - on that point, even. Unbelievable. But it was put in, and it got funded, and . . . I met the parents today and saw the direct results. I met the mothers out there, and I saw what a difference that's going to make. That's enough for me today, I'll tell you."

His voice changes on those five words: I met the parents today. His identification with them is nearly a physical thing. You can see their images in his eyes. You can hear their voices in the way that his changes. It's free of all the verbal confetti, and suddenly it's full of echoes in both its sudden precision ("Let the word go forth . . .") and its controlled passion (". . . and say, `Why not?' "). He's rounded out of his chair, and there's a flash to his eyes, and he's still a big man when he straightens up. "The point is to have some positive impact on people's lives," he continues. "The danger as a legislator is that you get involved with just passing the bill. You can lose the context of what passing the bill means, and then you're just shuffling papers, and you lose that emotional contact. Maybe some people could do it. I think I'd run dry pretty quick."

For all the echoes in his voice, the country is pretty plainly tired of the Kennedys. Except for him and his son, US Representative Patrick Kennedy of Rhode Island, no Kennedys can get elected anywhere anymore - not even the Kennedys named Shriver. It was the Kennedys who melted the wall between traditional political power and modern media celebrity. For a long time, they got what they paid for.

However, after the assassinations and after the dead woman in the car, the country started to get exhausted. It stopped treating the Kennedys like a public political treasure and began to treat the Kennedys like a public cultural bauble, not entirely different from Liz and Dick or, most recently, the Osbournes. They still provided the occasional media spectacular - Rose's funeral or John F. Kennedy Jr.'s sudden death. Otherwise, though, they were just a family, famous, surely, but also deeply troubled, full to the gun wales with drunks and lay abouts and public junkies. Edward Kennedy flamed out against President Jimmy Carter in 1980, and the raw material in the next generation was unstable. The country moved on, and the celebrity politics that the Kennedys had invented became so general that the Kennedys were rendered unremarkable in that regard.

"He has epiphanies," a friend told author Adam Clymer, but that's the old mythology talking. On October 25, 1991, Kennedy gave a famous speech at the Kennedy School of Government in which he said, "I recognize my own shortcomings, the faults in the conduct of my private life." By then, the woman in the car had been dead for 22 years, dead because of a situation in which alcohol and recklessness were intimately involved, and if this was an epiphany, it was a damned slow one. What he was on the day of the speech was an almost 60-year-old divorced man who drank too much, an aging father and uncle who was the caretaker for a spectacular array of functional and dysfunctional children, and that was all he was, and the barstools are full of them.

Those men have "problems" to overcome. Kennedys have "epiphanies."

As the late political essayist Walter Karp once wrote about him: "Kennedy is - a Kennedy. Great clouds of windbaggery befog and blind him, are bellowed forth to befog and blind him - the `Camelot legend,' the `Kennedy legacy,' the `presidential destiny.' " That was what he needed most to overcome - that sense that not only do Kennedys not cry, they do nothing that is not grand and royal and operatic and of great ritual import to the nation.

And there he is, rid of most of that now, 70 years old and 40 years a senator, and he stands for all the curdled glory, but most of all, for himself: Legislative lion and failed dauphin; dark prince and heir apparent; Capitol Hill grind and Palm Beach sybarite, talisman, and bogeyman; Camelot and Dallas and Los Angeles and Chappaquiddick. And then you realize the simple fact that he's not a Kennedy anymore, not in the fully mythological sense, anyway, and not as the sum total of his identity. He is the patriarch of a family, no longer of the family, a caretaker of wounded young adults, and not of a gaggle of miscreant royalty. He's the one who remembers all the birthdays.

"It's remarkable," says Senator John McCain, an Arizona Republican. "He's pretty much the patriarch of all of them, and they love him, and it's plain that he loves them."

Oh, he still uses the name and its attendant lore. "I stayed away from him for a period of time when I was a brand-new guy in the Senate," recalls McCain, with whom Kennedy last year worked on passage of the Patients' Bill of Rights. "You know, he's just one of those larger - than life figures that you tread carefully around."

There's an inner room in Kennedy's Washington office that's chock-full of family memorabilia, a great arc of history that's one of the greatest home-court advantages any senator has ever had. But he uses all of that family lore and legend only in the same way that West Virginia's Robert Byrd uses all of his honeyed constitutional fustian or McCain his experiences in Vietnam - as another tool with which to get the real work done.

"I think he's the greatest senator of the 20th century," says Senator Russell Feingold, a Wisconsin Democrat. "He's an incredibly smart, incredibly hard-working tactician of what goes on here. He understands the issues, and he really understands the institution of the Senate."

He squandered so much of the mythology - turned it into punch lines, really - that he was able to walk away from what was left, walk away and go to work, hashing out legislation, doing the grunt labor in the Senate for which his brother John never had the inclination and his brother Robert never had the time, walking into the wind, one step at a time, until he came to this point, 40 years on, when the relevant points of historical comparison are not his brothers but Daniel Webster and Henry Clay and Hubert Humphrey. Given the way that we do politics in this country today, he may be the last great senator. And, in the end, that may be enough.

"He's certainly the best legislator in his family," says Senator Orrin Hatch, a Utah Republican, Kennedy's close friend, and his ideological opposite. "Neither of those two brothers were in his league."

How do you assess it, then, all those many lives and the real one out of which this last one was made? How do you look at the ocean? Do you see the sum of it, or do you see only its parts? The deep, rolling waves or the small ponds where the ocean goes to die, brackish and foul, but the same water that elsewhere piles itself into a torrent and changes the climate? Are there places and lives so vast that there's room in them for every definition to be completely true and yet to be contradicted by another, no less true than the first?

Fame and celebrity are cheap and useful, but history, usually and stubbornly, finds some truth, and it is history that Edward Kennedy is playing for now, the vast and wide sweep of it, more than his brothers ever did, more than his brothers ever had a chance to do.

"There have been a lot of forces and experiences," he says. "But I don't dwell on that. I look forward to the future. I believe that, basically, it's the need that people have for the fairness of life, the ability to have some impact on that in a positive way.

"Maybe there'll be time later. But that's not today."

It has to have been a strange morning for him. The newspapers are full of reactions to the revelations that President John F. Kennedy's White House perhaps had a bit too much in common pharmacologically with Elvis Presley's Graceland. And, as he talks further about the people he met at the education center that day, his conversation returns to fits and starts. The fog moves in off the water, enveloping the John F. Kennedy Federal Building.

It is Friday, November 22.

Upstairs, Edward Kennedy talks about early childhood education and about the parents he'd met that morning. The significance of the date goes unremarked.

What if his name had been Edward Moore?

It was a great line, a defining line. Against any other candidate, and especially in this age of endless political reiteration, it would've been the knockout line. It became a cheap trope for easy newspaper columns. On August 27, 1962, at the close of their first debate prior to the Democratic senatorial primary, Edward McCormack looked at Edward Kennedy and said, "If his name was Edward Moore, with his qualifications - with your qualifications, Teddy, your candidacy would be a joke."

It bit so deeply because of the essential truth of it - the truth that, among other things, would doom Eddie McCormack. Back then, with Jack in the White House and Bobby as attorney general, Teddy Kennedy's candidacy for the Senate was an act of raw dynastic power. An obscure family retainer named Benjamin Smith held the seat until Kennedy was old enough to be elected to it. Once he was, he was sworn in, not at the beginning of the term in January 1963 but almost immediately after his election in November 1962, which is how he got the jump on seniority over Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, who was elected the same year. None of this would have happened if his name were Edward Moore.

If his name were Edward Moore . . .

He would not have served so long, if he'd served at all. He might not have served with more than 350 other senators. He would not have served with all three men - Everett Dirksen, Richard Russell, and Philip Hart - after whom the Senate office buildings are named. He would not have had his first real fight over the poll tax and his most recent one over going to war in Iraq. None of this would have happened if his name were Edward Moore.

If his name were Edward Moore . . .

If his name were Edward Moore, Robert Bork might be on the Supreme Court today. Robert Dole might have been elected president of the United States. There might still be a draft. There would not have been the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which overturned seven Supreme Court decisions that Kennedy saw as rolling back the gains of the civil rights movement; the 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act, the most wide-ranging civil rights bill since the original ones in the 1960s; the Kennedy-Kassebaum Bill of 1996, which allows "portability" in health care coverage; or any one of the 35 other initiatives - large and small, on everything from Medicare to the minimum wage to immigration reform - that Kennedy, in opposition and in the minority, managed to cajole and finesse through the Senate between 1996 and 1998, masterfully defusing the Gingrich Revolution and maneuvering Dole into such complete political incoherence that Bill Clinton won reelection in a walk. None of this would have happened, if his name were Edward Moore.

If his name were Edward Moore . . .

His brothers might be alive. His life might have been easier, not having mattered much to anyone beyond its own boundaries. His first marriage might have survived, and, if it had not, Joan Kennedy's problems would have been her own, and not grist for the public gossips. It might not have mattered to anyone, the fistfight outside the Manhattan saloon, the fooz ling with waitresses in Washington restaurants, the image of him in his nightshirt, during Holy Week (Jesus God!), going out for a couple of pops with the younger set in Palm Beach and winding up testifying in the middle of a rape trial. His second marriage simply would have been a second marriage, and Vicki Kennedy would not have found herself dragooned into the role of The Good Fairy in yet another Kennedy epiphany narrative.

All of this would not have mattered, if his name were Edward Moore.

And what of the dead woman? On July 18, 1969, on the weekend that man first walked on the moon, a 28-year-old named Mary Jo Kopechne drowned in his automobile. Plutocrats' justice and an implausible (but effective) coverup ensued. And, ever since, she's always been there: during Watergate, when Barry Goldwater told Kennedy that even Richard Nixon didn't need lectures from him; in 1980, when his presidential campaign was shot down virtually at its launch; during the hearings into the confirmation of Clarence Thomas, when Kennedy's transgressions gagged him and made him the butt of all the jokes.

She's always there. Even if she doesn't fit in the narrative line, she is so much of the dark energy behind it. She denies to him forever the moral credibility that lay behind not merely all those rhetorical thunderclaps that came so easily in the New Frontier but also Robert Kennedy's anguished appeals to the country's better angels. He was forced from the rhetoric of moral outrage and into the incremental nitty-gritty of social justice. He learned to plod, because soaring made him look ridiculous. "It's really 3 yards and a cloud of dust with him," says his son Patrick.

And if his name were Edward Moore, he would have done time.

He has spent so much of his professional life draining that line of its meaning - the defining line, what would have been the knockout line if his name hadn't been Edward Moore Kennedy. He went to the Senate. He respected its traditions. He learned from its elders; his office today is in the building named after Richard Russell, with whom, according to Adam Clymer, Kennedy first attempted to break the ice by mentioning that Russell himself had entered the Senate when he was 36. Yes, Russell replied, but I'd been governor of Georgia by then, and Kennedy had had the good grace (and the good sense) to laugh.

"At that time, I think, there was less partisanship," Kennedy says. "There was less pettiness, and there were stronger personal relationships that stretched across party lines. Now we're so evenly divided that little things become big things. That demeans the institution and demeans our relationships, and, anyway, I think the public sees through that."

He developed a thick skin and learned to leave the heat of the argument on the Senate floor. That's how Kennedy learned to move past that day in 1991 when, during the debate over the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court, his good friend Orrin Hatch appeared to summon up the Great Unmentionable. "Anybody who believes that," said Hatch, "I know a bridge up in Massachusetts that I'll be happy to sell to them."

To this day, Hatch maintains that any connection between his wisecrack and Chappaquiddick was unintentional. "I was really mortified," says Hatch. "A lot of my supporters loved it, and when I said I hadn't meant it, it drained some of the charm, some of the glory, out of it."

Of Kennedy, he says: "He's able to take criticism and let it wash off him like water off a duck. He's been praised so much and criticized so much that he just ignores it."

For his part, Kennedy plays his cards so close to the vest that, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, if they were any closer, they'd be behind him. "It's basically a result of understanding how the institution is working and how things get done and to know that intuitively," Kennedy says. "The other stuff is just part of the deal. If you don't learn it, you might as well not bother serving in the Senate. I can go down and fight with Orrin on fetal trans plantation and then testify with him on religious restoration when both were white-hot, and then we can go out later.

"Unless you work on that, there's very little left you can do. You can just be an advocate, and there's nothing wrong with that, or you can just be an accommodator, and you're not going to be a leader if you do that."

And that's the key. That's how you survive what he's survived. That's how you move forward, one step after another, even though your name is Edward Moore Kennedy. You work, always, as though your name were Edward Moore. If she had lived, Mary Jo Kopechne would be 62 years old. Through his tireless work as a legislator, Edward Kennedy would have brought comfort to her in her old age.

Stephanie Cutter, the senator's press aide, is concerned. An interview with Michael Myers, Kennedy's chief of staff, has wandered a bit beyond the comfortable boundaries, which are not expansive to begin with. "He said your questions were more about what makes the senator tick," the press aide says amiably. "You know, the senator doesn't do profiles. He's not that reflective about the personal stuff, about his brothers and all."

They're coddling him now, carefully monitoring how he is perceived, in the way earlier staffs used to hold their collective breath every time he went out of a Saturday night. (His staff went into an uproar in November over the comparatively benign revelation that Kennedy had promised $500,000 of his own money to help Boston win the Democratic National Convention in 2004.) "Teddy's office is in it for the legacy now," says an aide to another senator. "That's the focus."

Washington is as in hos pi ta ble to that legacy as it ever has been. The midterm elections handed Republicans effective control of all three branches of government. Kennedy campaigned all over the country for Democratic candidates; he was with Senator Paul Wellstone in Minnesota the morning of the day on which, later, Wellstone was killed in an airplane crash. On the day after the party's electoral thrashing, Myers called a number of liberal Democratic activists to reassure them.

"Thanks, Mike," one of them replied, "but the senator called an hour ago."

"He'll just keep on doing what he's doing," explains US Representative John Lewis, a Georgia Democrat whose experience with the Kennedys goes back to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. "There's no question that he's the embodiment of so much that we hoped for. Sometimes you have politicians come along, and they sort of talk about it, but they don't feel it. This man feels it."

It never was like working for other senators, anyway. "The anniversaries of his brothers' deaths were somber days. No one says anything to him, but it's obvious," recalls one former Kennedy aide. "Occasionally, you'll be sitting around with the senator, and, like a stream of consciousness, he'd tell a story about an interaction with the president or with Bobby, and it's just in passing. At the same time, there's the RFK awards every year, and the guy just can't get through the remarks."

He has not taken the deaths as a mass undifferentiated tragedy - the Kennedy Curse, which was part of the Kennedys as public property, which he has left behind him. But each of them clearly affects him in a different way. John Kennedy is usually "the president" or "President Kennedy," while his other brother is almost always "my brother Bob."

"In 1965, when my brother Bob came to the Senate, that was a different experience," he recalls. "I was the senior one here. That was kind of a role reversal. But not much of one. He was still the older brother."

So the legislative rec ord is the message, and the staff stays on it. Historically, Kennedy's staff has been a sort of Capitol Hill legend, the New York Yankees of policy wonkery. (Both Gregory Craig and David Boies, lawyers famous for, respectively, defending Bill Clinton's presidency and Al Gore's Florida recount bid, have worked for Edward Kennedy.) Perhaps the most underrated turning point of his career came in 1980. The Democrats had lost the Senate in the Reagan landslide, and Kennedy found himself in the minority for the first time. He had the choice of being the ranking minority member on the Senate Judiciary Committee or the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare. Kennedy chose the latter.

"He felt at that point that there was kind of a challenge to deal with the Reagan agenda and that this was the best place to do that," says Myers. At that point, his staff became not only the Senate's clearinghouse on a whole host of health and welfare issues; it also functioned as a kind of institutional memory at a time when politics in general seemed increasingly be reft of one.

"This is a guy who, the first thing he did in the Senate was take on the poll tax," says Bancroft Littlefield Jr., who was Kennedy's chief of staff through most of the 1990s. "The first issue he sinks his teeth into is trying to make it possible for black Americans to vote in the South. If he didn't have that passion for the underdog and for dispossessed people in his blood, that wouldn't have been the first thing he went after.

"To me, when you try to figure out Ted Kennedy, you have to understand those things he did early on, before the fancy advisers showed up," Littlefield says. "Then look at what happened between '95 and '98, when he's in the minority. The House passes the whole Contract With America in 100 days. All 10 bills, and nothing gets through the Senate, because Kennedy, basically, organizes the forces of resistance, and piece by piece, he brings the Democrats back, because he remembered what they stood for."

And he did it, in part, because he had learned the etiquette of the Senate as well as he had learned its rules. "There's one thing you can count on with Ted," says McCain. "He will always keep his word. There are a lot of people in Washington who waver in their commitments, but that's not him. The Patients' Bill of Rights was a tough fight. People were being cajoled by the special interests and by the White House, and he never wavered."

However, it's not a legislative laundry list that animates Kennedy, although he's made himself a genius at the mechanics of getting legislation passed. It is the ability to connect to the people for whom that legislation is intended ("I met the parents today") and to the people he needs to get done what he is trying to get done. Being a Kennedy comes into play only when it's useful.

For example, he forged a useful relationship with Clinton by dint not only of his legislative expertise but also through his personal charm. "Clinton was a Kennedy junkie," recalls Littlefield. "They got a big kick out of each other, and Kennedy was constantly worried about Clinton's progressive backbone." He shrewdly sized up Clinton and realized that it was a capital advantage to be the last person to see Clinton before the president made a decision.

In 1995, worried that Clinton was going to cave in to the Republicans on the budget, Kennedy got himself into an event at which Clinton was going to swear in new police officers on the White House lawn. Afterward, he followed the president across the lawn and into the Oval Office through the back entrance, while outside the main doors, Clinton's staff had gathered to keep Kennedy out.

Over the next two years, Kennedy maneuvered in a hostile Senate, mainly by working the system as ably as he worked the senators themselves. He got the Kennedy-Kassebaum Bill passed, and he won an increase in the minimum wage, even though the Republican leadership in the House had sworn up and down that it would never happen. And he did both of these in a bipartisan manner, because he understood not only how the Senate worked but how senators worked as well.

"There was a lot of self-flagellation at the time," Kennedy recalls. "And it seemed to me that there was a real opportunity to move creatively and aggressively."

This sort of thing effectively demolished Bob Dole. The Kennedy-Kassebaum Bill and the increase in the minimum wage were both enormously popular in the country and deeply loathed within the conservative caucus that was the power behind the Republican legislative agenda. At the time, Dole was running for president and trying to do so as an effective Senate majority leader, and he was so plainly impaled on the demands of these dissonant identities that he failed to satisfy anyone, including himself. On May 15, 1996, in a speech of breathtaking insincerity, Dole left the Senate. Bill Clinton was reelected that fall.

It takes a thousand little things to get this done: long, grinding sessions, a blizzard of memos and reports, the kind of vigor that John Kennedy never had. Learning the legislation and learning the people you need to pass it. Three years ago, McCain (along with Feingold) was named the recipient of the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award for the work the Arizona senator had done on campaign finance reform. The private dinner the night before the Boston ceremony conflicted with the 11th birthday of McCain's son, Jimmy.

"[Kennedy] said to me, `I'll make sure he has a good time,' " McCain recalls. "So we brought him up here, and he got a ride on a Coast Guard cutter around the bay, and he had two different birthday cakes, and people sang `Happy Birthday' to him twice, and he had an unforgettable time.

"To me, in so many ways, that epitomized Ted Kennedy - this incredible outreach to a little boy who, I mean, what is he to Ted Kennedy? It was remarkable to me."

A case study, then. Actually, a case study that begins with the study of a case.

In 1999, an 18-year-old named Jesse Gelsinger had volunteered to participate in a gene-therapy trial at the University of Pennsylvania. The researchers were trying to find a way to replace defective genes in order to treat patients with enzyme disorders. The genes were delivered by modified cold viruses. By the end of the first day, Gelsinger was ill. Two days later, he was in a coma. Three days after that, his family took him off life support. It soon became clear that Gelsinger had died because the researchers had gone beyond the limits of their protocols. Jesse Gelsinger's name soon found its way to Edward Kennedy's office.

"Jesse Gelsinger - that's the kind of thing that gets to him," says a former aide. "I mean, he's always done this ethics stuff, but then this Gelsinger thing happened, and he got on it like a rocket."

It always makes a difference when there's a person involved, a face on the issue. Kennedy picks it up from his reading, or in conversation with someone in his vast circle of acquaintances, or he reads something that he brought home in his briefcase, which the staff calls The Bag and treats as if it were ambulatory, as in "The Bag is leaving now." Whatever the case, he picks up an issue more quickly if he can put a face to it, if he knows the story behind it.

And this was an issue that was exploding. Genetic scientists and the biotechnology industry had thrown their science so far ahead, and had done it so fast, that the law and the culture were scrambling just to catch up. (In 2001, an estimated 20 million people were enrolled in medical research studies in the United States.) As a political issue, the protection of human subjects in medical research was the cutting edge of the cutting edge.

One night at about 8, just as he was getting ready to go home, a young aide on the Labor Committee named David Bowen prepared a briefing book to show to Kennedy the next morning. He showed it to his boss, a longtime Kennedy aide named David Nexon. There's only one thing missing, Nexon told Bowen: a legislative history of whatever Kennedy had previously done on the subject. Bowen went back to work.

"At about 3 o'clock in the morning," Bowen recalls, "I came to the realization of the depths of his involvement in these things." Kennedy had held the first congressional hearings into the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, and into the involuntary irradiation of patients at the Fernald School in Waltham, and into the CIA -backed LSD experiments in the 1950s that had resulted in the suicide of a researcher named Frank Olson.

"I think what I realized about working here," Bowen says, "was that you get to work for someone who was the original architect of research protections from the get-go and who now has the opportunity to re-engineer that same set of protections for a 21st-century research environment."

Meanwhile, Kennedy had Littlefield organize a dinner at which the experts in the field would come and brief him. "For these things, I might find the five best people in the country on it, and they'd fly in," recalls Littlefield.

"We're moving into these extraordinary breakthroughs," Kennedy says. "The rapid expansion of clinical research has put enormous pressure on oversight. It's basically gotten out of hand, in terms of their ability to do the job."

It was a remarkable demonstration of institutional memory, and Kennedy put it to work crafting legislation that was both precise and pragmatic. The regulation of these studies was disorganized piecework done by 15 different federal agencies. So, this fall, Kennedy proposed a new federal agency to regulate medical consent and an in de pend ent commission that would accredit any institution that sought to do medical research using human subjects.

Typically, he sought out a Republican, William Frist of Tennessee, a physician as well as a senator, as his cosponsor, the way he'd found Nancy Kassebaum on health insurance and John McCain on the Patients' Bill of Rights. The two had some differences - Frist wanted the accreditation procedures to be voluntary - but they seemed to be making progress until Frist got caught up in some internal politics within the Republican caucus.

Part of it is an omnivorous curiosity, particularly in the area of medicine and science, which became even more of a cause for him when a son, Edward Jr., lost his leg to cancer in 1973. The other part is his bullheaded insistence on moving forward, one step at a time, head down - of not merely winning, which was the original Kennedy curse, but of finding solutions.

"Curiosity is important," he says. "Maybe it's being curious or whatever the word might be - to be passionate about the subject matter and to have a combination of emotions and a willingness to listen to new ideas."

And now he's in the minority again, the way he has been for half of his Senate career, and without a Democratic president in the White House this time.

Kennedy is still optimistic, the way he was in 1980, when Ronald Reagan came to town, the way he was in 1994, when Newt Gingrich drove the agenda. "We were making good progress, but we weren't able to get it with Frist," he says. "I think we'll get it next year."

The young history professor came to the conclusion that Eddie McCormack might be right.

In 1962, Merrill Peterson was in his first job, teaching at Brandeis University, and Edward Kennedy went there, campaigning for the Senate. "He came out and made a talk and looked, frankly, like a lightweight," Peterson says. "He didn't look to measure up to his brother. He didn't seem to have much under him at all." Now a professor emeritus at the University of Virginia, Peterson is the author of The Great Triumvirate, a magisterial study of the senatorial careers of Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and John C. Calhoun in the years before the Civil War.

"I said to a colleague recently that he might be the greatest senator of them all," Peterson says. "Not just because of the time served but because of his excellence, and not just because I agree with him on most issues. I can't help with him but recall what a Philadelphia man once told Daniel Webster, when Webster was thinking of a presidential bid. This man advised him against it. He told Webster that he could be a senator until he died and still have a great career. And that's what happened.

"You know, I don't think there's much knowledge of history down in Congress these days. I think there might be a certain amount of knowledge since the New Deal, but that's pretty much it. History doesn't seem to inform their judgments much."

Look at the Senate now. Mavericks like McCain get marginalized, even by their own parties, in favor of technocrats and bloodless pedants, Kiwanis speakers and House members fighting far above their weight class. And there Kennedy goes, squashed, bowed and slowed, head down, moving forward, one hand keeping the other one still, and the place still moves. Glacially, but it moves. You play for history and you're playing for higher stakes, and fame and celebrity are just the $1 chips.

"I don't know if he'll have a marble head down here" in the Capitol, says Orrin Hatch, "but they'll find a spot for him somewhere."

On April 27, 2001, a bus carrying band members from the Oak Hill Middle School in Newton overturned on a highway in the Canadian Maritimes. Four children were killed. In Washington, a man whose child went to Oak Hill boarded an airplane in order to hurry home. He saw Edward Kennedy on the plane. The man told him what had happened. That's where he was going, the senator had replied.

At the school, volunteers gathered from all over Newton to help out. Along one wall, they'd hung broad swatches of blank white paper so that the children could express their sorrow and say their goodbyes. On the second afternoon of the melancholy vigil, a volunteer looked out and saw Kennedy, alone in the hallway, no aides around him and no cameras in sight. He was slowly, carefully, reading every single message left by every grieving child.

See him there in the hallway, alone, painfully private, and you see him as he is, the basic material of how he's built his career. You see all he's left behind - the life of metaphor and the life of symbol. He survived them both, until there's just the one life, 70 years on, just as if he'd been named Edward Moore. His tragedies are no greater or lesser than are those of the schoolchildren and their parents - no more important, no longer gilded for public consumption.

He was good with death that day. He's never lost there, not even in the deepest part of that inexhaustible mystery. His compass is true, and his touch never less than fine. And it is, of course, familiar ground. Two siblings killed in airplanes before he was 16 - he is the only Kennedy to survive an airplane crash - and then the garish public deaths, two of them in less than five years. Finally, the herculean effort of celebrating the achievements of the next generation, and of salvaging its sad flotsam - hapless junkies and drifting drunks, souls lost for a while or altogether.

And the dead woman, of course. He wasn't half as good there with dying as he's always been with death.

His best speeches are all eulogies. In 1999, at the memorial service for the six firefighters who died in the Worcester Cold Storage building, Kennedy gave a tribute that left Bill Clinton looking like a third-rate saloon singer condemned to follow Sinatra. He gave his greatest speech from a cathedral pulpit, over the coffin of his brother Robert. It was more than a remembrance. It was a foreshadowing of what would happen and a prayer, sort of, to be relieved of all those burdens that once looked so very much like the most golden advantages.

"My brother need not be idealized or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life," he said, in a voice like that of someone choking on blood. As though that were possible for any of them, given the lives they'd chosen to lead, but it hung in the air like a ragged prayer, hung there with the grief and the incense, palpable and yearning, a Pax vobiscum for so many souls, known and unknown, not least of all his own.

Charles P. Pierce is a member of the Globe Magazine staff.

www.boston.com/bostonglobe/magazine/articles/2003/01/05/kennedy_unbound/