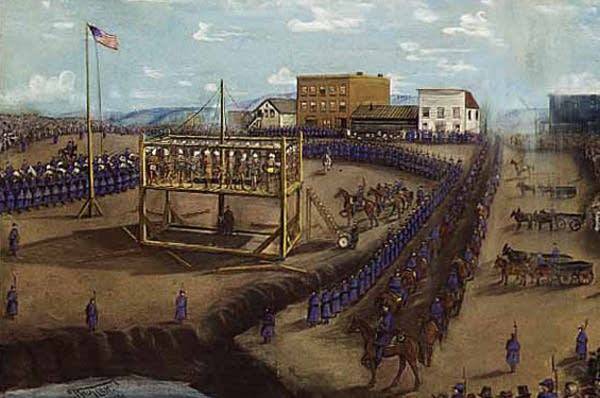

Illustration depicting the hanging of 38 Dakota men at Mankato, Minn. on Dec. 26, 1862.

It was Dec. 6, 1862. On President Abraham Lincoln’s desk lay a list of 303 Dakota people who were accused of everything from rape to murder.

These accusations came after Dakota warriors in southern Minnesota took it upon themselves to do something about the starvation and loss of millions of acres of their land caused by white settlers in what’s known as the Dakota Uprising. That battle ended with the deaths of 150 Dakota and nearly 1,000 white settlers during the fighting itself — but the true numbers of Dakota casualties over the next several years are still, to this day, untold.

There were no lawyers and no witnesses at the trials of these Dakota people and some were sentenced within mere minutes. In the end, Lincoln and his lawyers combed through the charges and eventually decided that 39 would die. One man’s sentence was commuted minutes before heading to the gallows, but the 38 about to die sang Dakota songs and held hands as they plunged to their deaths at the end of a rope. To this day, it remains the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

After the executions, some 1,700 Dakota elderly, women, and children who had nothing to do with the uprising were placed into concentration camps. Those who survived starvation and disease there were shipped off to reservations in South Dakota, where conditions were no better.

These Dakota people had lived in Minnesota for hundreds of years before white settlers had ever set foot there, and now, they were gone.

The Treaty That Started It All

Signing of the 1851 treaty.

By the time the Dakota wars broke out in 1862, most of the Dakota were starving. This was due to a treaty that they’d signed 10 years before that had cost them 25 million acres in exchange for promised gold, cash, and food. When it came time to deliver on this, however, the U. S. government changed the terms and instead sent the payments to the white settlers who sold goods to the Dakota.

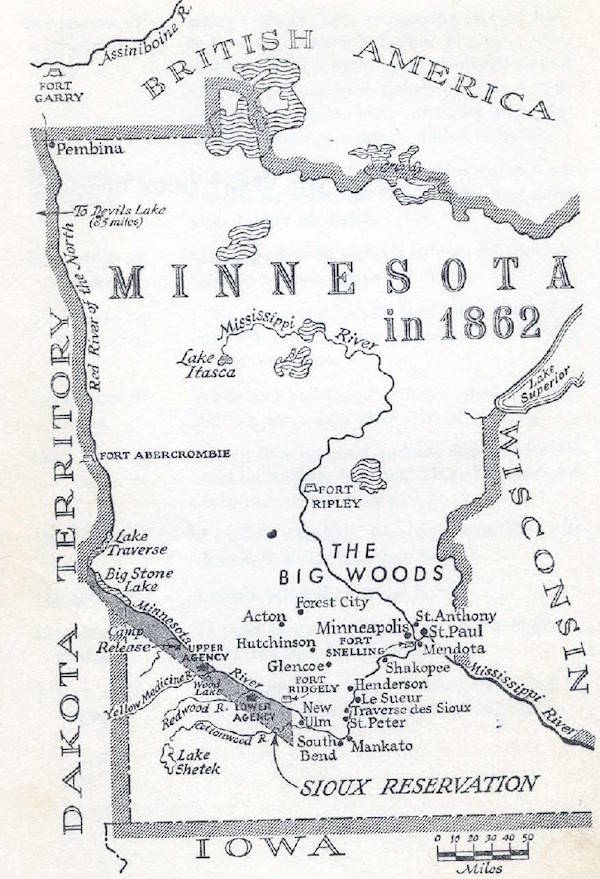

A map of Minnesota in 1862.

Finally, in a cruel natural disaster, the decimation of the Dakota corn crop in 1861 by a “cutworm” infestation meant the vital crop the Dakota had been counting on for survival would not be harvested.

Thus, by the summer of 1862, the Dakota people were absolutely desperate.

Desperation Turns To War\

There were two key incidents that started the Dakota Uprising of 1862, both on the same day: Aug. 17. The first came when desperate Dakota people broke into a government “agency” (administrative offices that managed the reservations and held stores of food) known as the Upper Agency (see map above) to take flour and other staples. This incident spread fear and anger among the white settlers and other agencies of the federal government.

The other event was when, on the same day as the agency storehouse incident, a small group of four young Dakota warriors came back emptyhanded from a hunt. They then tried to steal eggs from a small white settlement near Acton — about 60 miles West of Minneapolis. The young men were caught doing so, and in the ensuing back-and-forth, the white settler family who owned the chickens was killed.

Sensing what was coming next and desperate for basic food supplies, Dakota warriors called for an all-out war with the white settlers and traders, as well as with the U.S. government itself.

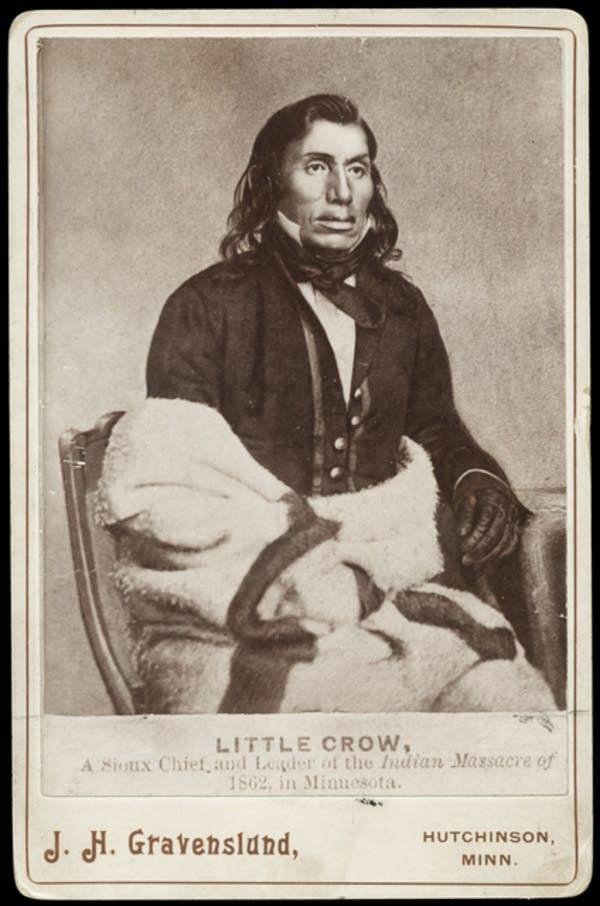

Chief Little Crow

Chief Little Crow, whose Dakota name was Ta Oyate Duta, disagreed with the sentiment of warring with the white settlers and the federal troops because he’d traveled to Washington, D.C. four years prior and knew just how many there were in the country. He warned them with these prescient words: “If you strike at them they will all turn on you and devour you and your women and little children.”

Still, he resolved to lead the tribe’s attack force and die with them if he had to. The warring members of the Dakota tribe searched out local settlers and once again began with the agencies. This is also where the merchants who famously stole the Dakota cash payments had storefronts.

The “Lower Sioux Agency,” which was actually on the tribe’s own land, was their first target. They took food supplies, set fire to some of the buildings, and killed about 20 of the white men who worked there and attempted to defend it.

Fort Ridgely was next to be attacked, though the warriors were eventually pushed back. They then headed from town to town, killing as they saw fit, sparing some settlers who they knew to be friendly, and taking what food they could scrounge up.

This continued until finally, after the Battle of Wood Lake 36 days later, the Dakota Uprising of 1862 was over. Total numbers aren’t certain, but estimates are that 500 — 1,000 of the white settlers and about 100 Dakota lay dead.

The Inevitable Retribution

The fighting was over, but the sentiment of most of the Dakota people had been decidedly against what the warriors had done. They knew what could come of it.

And, indeed, it did.

Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey had declared just a few weeks before the end of the uprising what he intended to do:

“The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the State. If any shall escape extinction, the wretched remnant must be driven beyond our borders, and our frontier garrisoned with a force sufficient to forever prevent their return.”

Indeed, the state eventually raised the bounty on Dakota scalps from $75 to $200 — $2,500 apiece in today’s dollars.

After the uprising, the head of the military for the area, Colonel Henry Sibley (who was the main architect of the flawed treaty to begin with), promised security and safety for the remaining Dakota people if they came forward. The warriors who had caused death and destruction had already fled the state or were captured. Those who did come forward were old men, women, and children. They were hunger-marched for several days to Fort Snelling, near St. Paul.

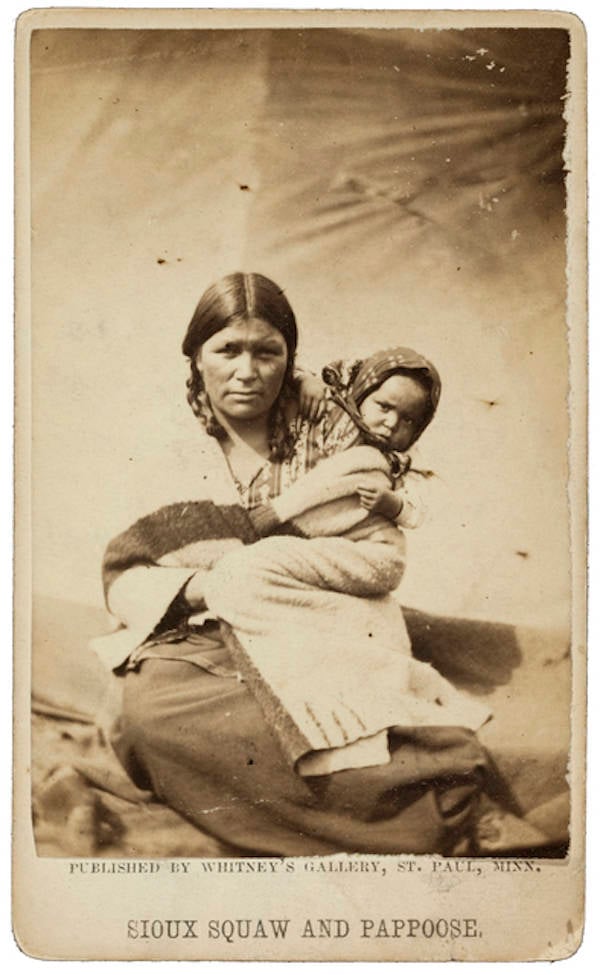

It was “essentially a concentration camp,” said historian Mary Wingerd, “where they were kept until the spring of 1863. And then they were transported to a reservation — Crow Creek, South Dakota. It was in Dakota Territory, which was the next best thing to hell. And the death toll was just shocking.”

“They lost everything. They lost their lands. They lost all their annuities that were owed them from the treaties. These are people who were guilty of nothing.”

A Dakota woman and her child in the concentration camp at Fort Snelling. 1862 or 1863.

This, of course, followed the execution of the 38 Dakota prisoners on Dec. 26, 1862 in Mankato — the largest mass execution in American history.

After the execution, the rest of the Dakota people were effectively banished from the state forever.