Workers, Banking, and Crisis in Mexico

Thomas Marois

In the nexus between workers, banking, and crisis, the case of

The role of workers and the value they create should be examined at two levels: 1) the general society-wide relationship between labour and finance and 2) the specific employment relationship between bank workers and banks. Examining both levels is necessary for understanding how the banks have benefitted from neoliberal strategies of development in

Historical Backdrop

Since 1982,

The third structural shift, which increased the dominance of foreign ownership and control, began initially in the wake of

In

Given this concentrated structure, how did the Mexican banking sector perform during the global financial crisis of 2007-2009? When Lehman Brothers collapsed in mid September 2008 and the global financial system teetered on the edge of the precipice in October 2008, there was an unavoidable impact on the Mexican economy and knock-on effects on its financial sector.

International flows of capital into

During the height of the crisis, the central bank, Banco de México, resorted to selling, in less than 72 hours, a record 11% of its reserves (worth well over $6-billion (

However, the banks in

Socialization of Banking Debts

Why have the banks in

This transformation has enabled governments to socialize private financial risk in times of crisis in

When the 1995 banking crisis broke, the Ernesto Zedillo government (1994 to 2000) socialized vast amounts of private bank debt that had gone sour. The Banco de México coordinated a huge bank bailout through Mexico’s banking insurance fund, Fobaproa. This involved the injection of U.S. dollar liquidity, the temporary and permanent recapitalization of banks, and individual debt restructuring programs. This rescue was necessary if and only if the Zedillo administration wanted to remain committed to implementing neoliberal strategies of development.

By early 1998, the cost of the bailout had grown to $60-billion (

The costs of providing public guarantees for private financial risk that had gone sour became the perpetual collective responsibility of present and future generations of Mexican workers – the ones responsible for creating the income needed to service the debt. The Mexican process of the socialization of bank debts typifies all recent state-initiated neoliberal bank rescues.

Increased Exploitation of Bank Workers

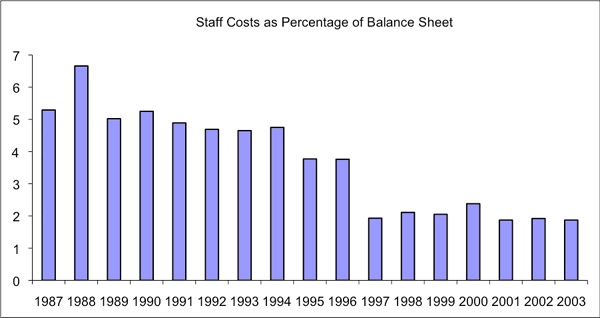

The post-1980s transformation of employment relationships between bank workers and the banks in

Beginning with the de la Madrid presidency, under the aegis of state ownership from 1982 to 1991-92, and despite being unionized since 1982, Mexican bank workers suffered 10 years of real wage reductions in order to help banks improve productivity measures. When President Salinas rapidly privatized the banks in 1991-92 – and 18 state-owned banks became 18 private domestic banks – the pressure to drive up bank worker productivity only intensified.

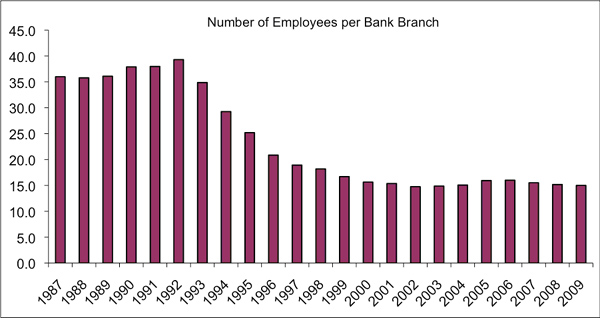

Intense inter-bank competition ensued as the new private owners sought a rapid return on their investment. One prominent strategy involved expanding bank branches in order to capture additional domestic savings that could be used in the lucrative business of supplying public credit and consumer credit. But the expansion of branches occurred without increasing the numbers of bank employees.

From the first sell-offs of the state banks in 1991 until the peso crisis in 1995, the number of bank branches in

It was at this point that foreign bank capital began to flood into

Since 2002 and under the predominant control of foreign bank capital, the rapid expansion of branch networks has continued. By the end of 2009, nearly 4000 new branches had opened – representing an expansion of over 50%. However, during this period the number of bank employees grew by a similar percentage. This suggests some leveling off of levels of labour productivity demands, relative to branch expansion, as banks in Mexico focused on lucrative operating strategies like servicing state debt and consumer credit.

The dramatic increase in labour productivity, in conjunction with the socialization of bank debt, contributed to the banks’ relatively high levels of profitability by 2007, when the

Finance and Union Struggles

To be sure, the fattening of bank profits has had much to do with favorable institutional reforms, higher fees and commissions, and lucrative state debt and consumer credit operations. Still, these important factors do not take account of what has been largely ignored in the literature but affirmed by no less than the Deputy Governor of the Bank of Mexico, José Sidaoui (see Sidaoui 2006): the expansion of banks’ profits has been closely tied to a contraction in operating expenses, which has been due mostly to reductions in the number of bank employees per branch.

At the same time, one must underscore the central point that the apparent resilience of

Since the 1990s, neoliberalism has entered a new phase in which the continuous enrichment of the financial sector has been built on the basis of shifting the burden of financial risk onto labour, both directly and through society-wide measures. These practices are not limited to

Strategies to overcome the shifting of private financial risk onto the working class must be multi-layered. Where there are bank unions, as in

Thomas Marois teaches Development Studies at the

www.globalresearch.ca/index.php

March 12, 2010