21 year old Virginia man is recruited over the internet by the 'Defense Intelligence Agency' to rob banks in order to test police response times

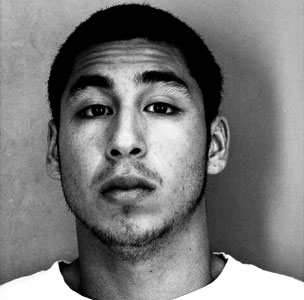

H. Torres

H. Torres

Torres’s unlikely entry into the covert world of retail bank security testing had begun seven days earlier, he said. He had returned home from unloading trucks at Target when his phone lit up with a text message from an old friend. “Hey, I got this job for you where you’re going to get paid 25K,” Carolina Villegas wrote. “Doing what?” Torres asked. “Robbing banks,” she texted.

That night, Villegas called Torres with instructions from Theo: More banks tomorrow. Bring friends. Torres was scheduled to work, but Villegas said it wasn’t a problem: Theo would take care of it. After a call to Target and a faxed doctor’s note, Torres was free to focus on his new job.

Six hours after Torres was arrested, Detective John Vickery of the Fairfax County police got a call on his cell phone from an unfamiliar number with an Oregon area code. It was Theo. “Where is he? What have you done with him?” he demanded. “You can’t make people disappear—only we can.”