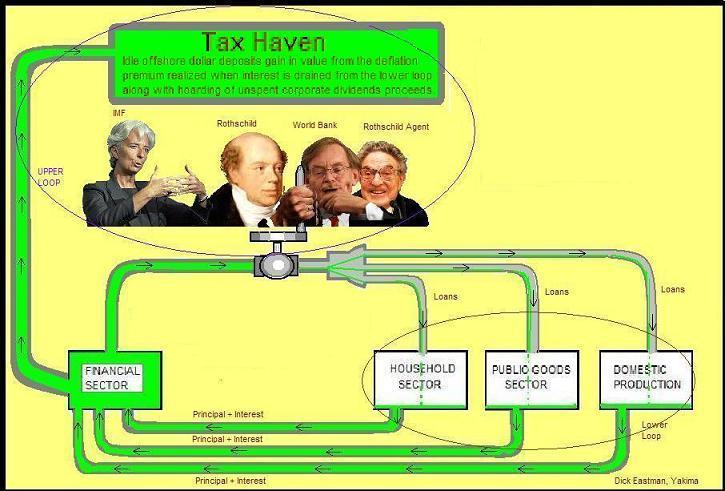

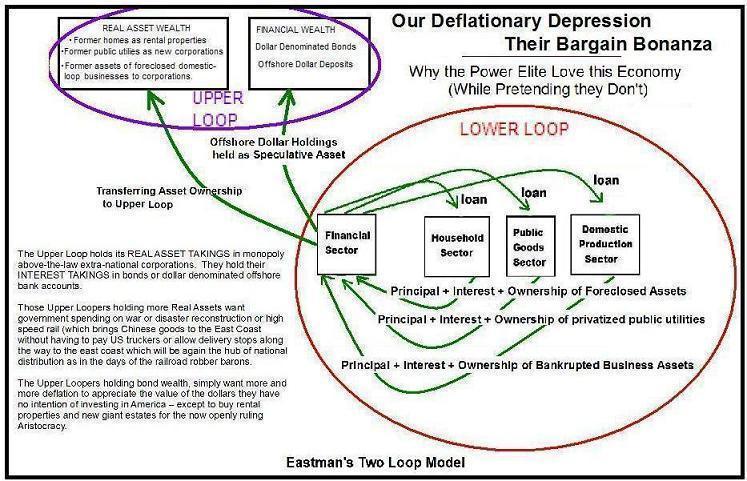

So you don't think the interest we pay and the monopoly premiums we pay are being hoarded to earn deflationary premium?

Dick Eastman

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Countries that lose tax revenues become more dependent on foreign aid. Recent research has shown, for example, that sub-Saharan Africa is a net creditor to the rest of the world in the sense that external assets, measured by the stock of capital flight, exceed external liabilities, as measured by the stock of external debt. The difference is that while the assets are in private hands, the liabilities are the public debts of African governments and their people.

TAX HAVENS CAUSE POVERTY THROUGH DEFLATION

- We oppose tax havens and offshore finance

- We support transparency and we oppose corruption

-

We support a level playing field in competitive markets

Tax is the foundation of good government and a key to the wealth or poverty of nations. Yet it is under attack. These places allow big companies and wealthy individuals to benefit from the onshore benefits of tax – like good infrastructure, education and the rule of law – while using the offshore world to escape their responsibilities to pay for it. The rest of us shoulder the burden.

Tax havens offer not only low or zero taxes, but something broader. What they do is to provide facilities for people or entities to get around the rules, laws and regulations of other jurisdictions, using secrecy as their prime tool. We therefore often prefer the term "secrecy jurisdiction" instead of the more popular "tax haven."

The corrupted international infrastructure allowing élites to escape tax and regulation is also widely used by criminals and terrorists. As a result, tax havens are heightening inequality and poverty, corroding democracy, distorting markets, undermining financial and other regulation and curbing economic growth, accelerating capital flight from poor countries, and promoting corruption and crime around the world.

The offshore system is a blind spot in international economics and in our understanding of the world. The issues are multi-faceted, and tax havens are steeped in secrecy and complexity – which helps explain why so few people have woken up to the scandal of offshore, and why civil society has been almost silent on international taxation for so long. We seek to supply expertise and analysis to help open tax havens up to proper scrutiny at last, and to make the issues understandable by all.

The fight against tax havens is one of the great challenges of our age. Our approach challenges basic tenets of traditional economic theory and opens new fields of analysis on a diverse array of important issues such as foreign aid, capital flight, corruption, (continued below)

The Tax Justice Network promotes transparency in international finance and opposes secrecy. We support a level playing field on tax and we oppose loopholes and distortions in tax and regulation, and the abuses that flow from them. We promote tax compliance and we oppose tax evasion, tax avoidance, and all the mechanisms that enable owners and controllers of wealth to escape their responsibilities to the societies on which they and their wealth depend. Tax havens, or secrecy jurisdictions as we prefer to call them, lie at the centre of our concerns, and we oppose them.

|

President Obama and his Defense and State Secretaries' Leon Panetta and Hillary Clinton have increased the wealth of weapon contractors with our tax dollars beyond comprehension:

"The price tag for the remote control drone war keeps rising," explained Jefferson Morley in his Salon column. "Americans are paying an extra $100 million a month because of the drone war in Afghanistan and Pakistan, according to Defense Secretary Leon Panetta."

(http://www.salon.com/2012/06/19/drones_spur_debt_and_polio/singleton/)

There is no justification for U.S. drone attacks which have terrorized the residents of the region by randomly killing children and civilians in Afghanistan as well as patrol soldiers on the border of Pakistan.

Meanwhile, as unemployment and poverty rises and as more and more cities go bankrupt such as Scranton, Pennsylvania, (http://www.businessinsider.com/scranton-mayor-slashes-all-public-worker-wages-2012-7) where firefighters and police workers' earnings were slashed to the minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, as climate change disasters sweep the country, leaving crops barren from droughts, and as wildfires consume entire communities and forests, as electrical power outages from hurricane force winds during the hottest summer on record create more burdens and suffering for Americans, the Pentagon and White House team came up with another brilliant idea to increase the wealth of contractors: they approved of more spending, an estimated $200 billion for thousands of surveillance drones that will be used to illegally spy on Americans. "US taxpayers will have invested about $11.8 billion on a single drone among many, (Reapers) (http://www.knowdrones.com/DRONE-FAQ.pdf). It's hard to be sure what the exact cost figures are-but between the drone wars and domestic drones-it adds up to billions of dollars.

So in addition to the drone wars, taxpayers will spend billions of dollars more on drones used to spy on us-while an estimated 6 million children go hungry every night in this country, and while public services, fire and police departments are slashed because there is no money to support them.(http://www.politicolnews.com/domestic-drone-laws-to-monitor-americans-draws-critics/)

Raising taxes won't fix our economy when we have a huge perpetual leak (weapon contracts) in the ship that is draining the country dry, when we have mismanagement of tax dollars that serve the top 1 percent at the expense of the entire country.

This is what happens when politicians have the power to spend money that doesn't belong to them. Certainly if the surveillance drone allocation were put to the voters, it would be flatly rejected. Spending billions of dollars on drones in the middle of a dire economic depression is not only immoral, when our tax dollars are supposed to be used for public services to improve the well-being of our lives, it's also as unconstitutional and as un-American as it gets.

Spying on American citizens presents a clear and present danger to the Rule of Law. When a government intrusively spies on its citizens, it is called a totalitarian state. Just as President Bush claimed unlimited and unchecked power, President Obama has also adopted the same extremist position by opting to ignore the surveillance laws pertaining to the FISA court. ¹

Regarding the question of abuse of executive power, it's worth repeating the question that Sen. Russ Feingold asked Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, January 31, 2006:

"Does the president...have the authority, acting as commander in chief, to authorize warrantless searches of Americans' homes and wiretaps of their conversations in violation of the criminal and foreign intelligence surveillance (FISA) statutes of this country?"

Gonzales dodged the question, but we know that a president does not have that authority. Furthermore, there is nothing reasonable about spying on every single citizen. If we still had a functional system of checks & balances, Bush would have been impeached for committing high crimes and misdemeanors. But Congress only impeaches presidents for lying about sex affairs.

Illegal surveillance is far more threatening to citizens of this country than trumped up threats of terrorism. A few days ago, Naked Capitalism reported that "Drone pilots may practice spying activities by tracking civilian cars." The feds have absolutely no constitutional right to invade the privacy of our homes or to track civilian cars without our consent. (Drone Pilots May Practice by Tracking Civilian Cars, and More) (http://truth-out.org/news/item/10214-election-countdown-2012-drone-pilots-may-practice-by-tracking-civilian-cars-and-more)

Under the Fourth Amendment, all searches, whether conducted with or without a warrant, must be "reasonable".

Spying on everyone is not reasonable. (http://www.aclu.org/blog/tag/domestic-drones) It is, as Glenn Greenwald expressed it, "wholly antithetical to the system of government under which Americans have lived for more than two centuries." In addition to tapping our phone conversations and tracking our internet interests, from the books we buy to the movies we watch to the organizations and blogs that we visit, the president approved of sending thousands of drones into the airways that will be used to spy inside our homes at the cost of billions of tax dollars. They can follow us from room to room, listen to what we're saying, they can photograph us, and they can send all the information collected directly to the NSA (National Security Agency). Perhaps the drones will capture millions of pictures of starving American children squeezing ketchup packages for food?

Ironically, we are paying for their criminal surveillance activities with our tax dollars. Shouldn't our tax dollars be used for public benefit or debt retirement? No money for public goods, but plenty of billions for unnecessary and illegal drones and the expansion of drone wars in the Middle East.

....-

thought provoking article of the day

What does the pursuit of happiness have to do with economics?

Luigino Bruni

“Men’s deepest, strongest yearning is to achieve

happiness ... Economics shares no less an aim, which it

serves as the means to an end. Economics cannot

therefore dwell, as some believe, on research and the

doctrine of half-measures to increase production;

rather, its concern with production is useful only in so

far as this is capable of increasing men’s opportunities

to live happily” (R. Michels).

1. In the beginning there was happiness

Happiness has a long tradition in economics. Modern economics has it origins in the

Mediterrean as the science of “public happiness”, where the adjective “public” put the accent also

on the social nature of happiness.

The Genoa born, naturalised Neapolitan writer, Paolo Mattia Doria began his Of Civil Life

(1710) with the phrase: “The first object of our desires is without doubt human happiness”. The

concern for happiness is a theme shared by Italian economists, particularly Neapolitans, since the

eighteenth century.

Antonio Genovesi (1963, 1976) is perhaps the foremost theorist on the relationship between

public happiness and civic virtues, but the theme was linked to the Italian economists, who, as the

Italian Achille Loria wrote at the end of the nineteenth century, “deal not so much with the wealth

of nations, as Adam Smith did, but rather with public happiness” (Loria, 1904, p. 85).

We find happiness in the titles of writings by Giuseppe Palmieri from Lecce (Reflections on

Public Happiness, 1787), of Ludovico Muratori (On Public Happiness, 1749), and in the work of

the Milanese Pietro Verri who insisted that “the treatise On Happiness has a very common theme,

on which many, many others have written” (Verri, 1963, p. 3).

For two centuries happiness has been overshadowed as a theme in economic thought, and its

return today is one of the most interesting aspects of the panorama of economic theory.

The rediscovery of the Neapolitan school of civil economy can be a source of inspiration in

understanding new trends in economics. The dialogue in civic life, or polis, is essential for an

understanding of the Neapolitan school.

2. The current debate

The return of happiness as a theme in economics is due to the emergence of a new fact.

Economists themselves has always known that wealth alone does not bring happiness. The often

implicit hypothesis underlying economic analysis was that even if wealth or economic well-being

did not always bring a “proportional” increase in happiness, it did not would not however entail its

diminution.

For this reason, especially in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, economics has confined its concern

to a sphere much less complicated than happiness: that of wealth or (economic) well-being –

realising of course that much of peoples’ happiness depends on non-economic factors such as

relationships and emotions, which have nothing to do with the market.

The theory of relative income offers some interesting clues as to why an absolute increase in

per capita income does not bring an increase in happiness: only if our income level increases

relative to that of others does our happiness increase.

Is this explanation enough to account for the paradox of happiness?

Another interpretation for the reason why happiness is diminishing in many “advanced”

societies, involves the classical idea of happiness, the Aristotelian eudaimonia.

3. The first thoughts

All Greek philosphy sought to make a distinction between fortune and happiness. The

mythical period, which we understand as the Greek-Classical period, has achieved a fusion of the

two words.

eudaimonia meant one had a good demon, or good fortune. Happiness and fortune were two

identical concepts. This original meaning is retained in modern Anglo-Saxon languages: in German,

glück means both happiness and fortune, and in English, “happiness” comes from the verb “to

happen”.

With Socrates and then Plato and Aristotle, the word eudaimonia became laden with new

meanings and the idea gained currency that man, with his choices and his liberty, could become

happy, even against the strictures of fate. And the way to reach happiness is to lead a good life, a

virtuous life: virtue becomes the way to happiness, but the virtues cannot be instrumental, but an

end in itself, the practice of which indirectly bears the fruit of happiness. The concept of virtue

therefore constitutes the instrument that helps us to distinguish fortune from happiness.

Virtue is synonymous with a flourishing life, of human rebirth, of the man who is well and

therefore happy. Tragedy, the ethic of Plato and Aristotle, can be read as an attempt to dissociate

happiness from fortune, through the virtues.

happiness as something independent from fate, Plato recommends that philosophy be detached from

external circumstances, including relationships with other people, so that our happiness is not

dependent on their choices. Aristotle’s vision however, is fundamentally different. In the

Nichomachean Ethics he asserts the essentially social, relational nature of eudaimonia: it is largely

dependent on civil virtues, on intimate, non exploitative relationships: on relational goods

(Nussbaum 1986).

In Plato’s view civil life is synonymous with relational goods characterised by love/friendship

(love that does not diminish the other); by civic commitment and the citizen’s commitment to the

society of the polis.

Aristotle had a more complex vision in his Ethics, where he focused on friendship and

asserted that: by relying on others, one is not independent, but one cannot be happy in isolation. All

levels of human development, i.e. men in a state of happiness, have a need for friendship.

The common need to separate happiness from fate depends also on the choices made by

others.

The vita civil, or civic life is the place where happiness reaches a state of perfection, but at

the same we know that from the ontological point of view, the good life is fragile and vulnerable. If

the individual renounces relations with others in order to be happy, he will never attain happiness

which is paradoxical by nature anyway. In other words – and this goes against the grain of common

opinion - it is a paradox that exists at the heart of the “sincere” interpersonal relations upon which

happiness depends.

4. The Italian tradition of public happiness

Economists of the so-called classical period of economic science paid close attention to the

social and psychological factors that influence the dynamics of consumption .

However, these were rarely incorporated into theory, but confined to social or ethical discussion

(we need only think of the social and psychological analyses found in the non-economic works

of Adam Smith).

The analysis of consumption was not differentiated from social, ethical or political analysis.

The early economists a generally had a highly socialised approach to economics. Subjects were

seen to be immersed in a network of personalised relationships. Consequently, consumption was

also placed in a social and relational context , and was studied as such.

This is very true for the tradition of civil economy, a largely Italian phenomenon, even if in

the broadest sense it can also be said of most of the classical economists from Smith to J.S. Mill,

and even to Bentham.

After the classical age, and until recent times, the development of economic science can be said

to have gradually jettisoned its concern for the social and interpersonal dynamics of civic life.

Important exceptions to this rule do however exist: Malthus, Senior, Edgeworth, Marshall,

Veblen.

In 1642 Thomas Hobbes wrote De Cive, (The Citizen) in a historico-social context, where

man was defined by his fear of being killed. In fact, with Hobbes we see the death of the social

aspect and the birth of the political. There was a shift away from the civil aspect (the polis and the

civic dimension) towards the political. The elements of liberty were abandoned in favour of those of

a political character.

Alberto Bobbio suggests another reading of Hobbes by considering society as an

intermediate level; man is born, grows, is married, starts a family. Many families make up society.

Civil society, according to Bobbio, therefore becomes uniform.

However Hobbes denies fraternity, to arrive instead at equality and liberty, hoping to reach

the final destination of having free and equal people. Hobbes is therefore important for an

understanding of the current situation of civil economy.

Political economy is characteristic of English and Scottish economic thought while civil

economy, with its origins in an Italian city – Naples, has the objective of protecting the three

principles of equality, fraternity and liberty.

Enlightenment Naples cannot be avoided in any reconstruction of the relationship between

economics and happiness. The leading economist of the Neapolitan school was the Salernitan

Antonio Genovesi (1713-1769). “Civil Economy” was in fact the expression used by Genovesi to

describe a notion of economic activity where the civil virtues of reciprocity, shared trust and mutual

confidence were considered essential for the development of a nation.

This economist of the Kingdom of Naples developed an idea of economics where the role of

civil society and the informal network of interpersonal relations was central.

“Civil”economy is distinctive in comparison with both the political economy of the Anglo-

Saxon world and the public or social economy typical of France and other Italian writers. Although

these issues may highlight the differences between the new science and domestic or private

economics, the civil economy of Genovesi and the Neapolitan tradition present some characteristics

that render it a system in its own right. At the one time there is the emphasis placed on civil, or

urban life and the Genovesian emphasis on ‘civic’ bodies, particularly the family, which constituted

the heart of the city and of the nation. “The rights of families arise out of the rights of individuals

and their various combinations; the rights of political bodies likewise come from the rights of

families”.

On the other hand, in Genovesi’s view, not only is civic life unopposed to happiness, it is

seen as the place in which happiness can be fully achieved – a process assisted also by laws,

commerce and trade, and the civic bodies in which men exercise their sociality: “If on the one side

the company of men can beget some ills it also stands as a custodian of life and property, which

brings many pleasures, unknown to men of nature” (Diceosina, p. 37).

This is a cornerstone of the traditional Italian civic vision ( (la vita civile), from Petrarch to

G.B. Alberti, from Valla to Guicciardini and many others, who, having perceptively observed in

their own towns the birth of that certain something new that would lead to modern capitalism,

wondered whether the search for gain, lucre, profit, luxury and interest was merely to be

condemned (as a certain classical-Thomist philosphy would demand), or if, under particular

conditions, it could even be encouraged for the common good.

Closer still to the thinking of Genovesi was that of his master Vico, who in New Science (third

edition 1744) wrote that the legislation and regulations of civil society, unlike philosophy, which

considers man as he “ought to be”, considers man “as he is, to make use of him for the good of

human society”.

We now move on to Genovesi’s idea of happiness, which presents important elements

overlooked in the current debate on economics and happiness. I chose this author not only because

he is the leader of the Neapolitan school, centred more than any other school on ‘public happiness’

but also because he appears to be an economist who attempted to engage the new Enlightenment

instances in the classical Greek (Aristotelian) and Latin (scholastic) tradition”, in the Italian

humanist tradition of the “civic life” , and linked them with the original thought of G.B. Vico, one

of his masters. There are no doubts surrounding the classical credentials of the thought of Genovesi:

one only has to think of his emphasis on “public faith” and the virtues, or to remember that he

taught moral philosophy in the same university faculty occupied by Saint Thomas, or that Aristotle

is by far the most quoted author in his works. Nor can the modernity of his thought be brought into

question: Galileian and Newtonian themes are present in his work, as are the Cambridge Platonists,

the French Enlightenment thinkers, Descartes and Locke. In fact, the ‘Lockist’ elements of his

philosophy and theology was the target of the fiercest criticism by the ecclesiastical authorities.

Happiness is paradoxical in nature precisely because it is constitutively social and relational.

We see Genovesi’s understanding, in keeping with the classical tradition, that a “good life” cannot

be lived if not with and because of other people (making others happy). This is why we cannot fully

control it: the completeness of a human being depends on reciprocity, but to get this requires

engaging in gratuitous or selfless actions, in the hope of reciprocal responses (Plato and other Greek

philosophers warned that this involves dangerous risks). Without this willingness, genuine

reciprocity cannot be engendered.

“All our economists”, wrote the Italian economist Achille Loria at the end of the nineteenth

century, reporting a widely circulating thesis in the Italy of that time, “Are occupied, not so much

with the Wealth of Nations, as Adam Smith was, but rather with public happiness” (Loria, 1904, p.

85).

Paolo Mattia Doria began his On Civil Life (1710), a text that became an important source

for the development of the thought of Genovesi and the Neapolitan school, with this phrase: “The

first object of our desires is without doubt human happiness”.

at that time: from Giuseppe Palmieri (Reflections on Public Happiness), to Ludovico Muratori (On

Public Happiness), or Pietro Verri who stressed that “the treatise On Happiness has a very common

theme, on which many, many others have written”.

Although the Kingdom of Naples economists and indeed much of the Italian tradition attach

great importance to public happiness, making a principal characteristic of the Italian classical school

of economics, it does not mean that the theme was the prerogative of the Italy alone. French

philosophers and economists such as Liguet, Maupertuis, Necker, Turgot, Condorcet, Sismondi, all

included happiness in their analyses.

But the fact remains that English economic thought, as developed by Smith and later

Ricardo and the other classicists, has not focused on happiness but the wealth of nations.

Vico, Galliani and Genovesi also admit the idea of providence, as defined by the Scots,

which transforms private wealth into public assets. The city of Naples is aware that providence

transforms private wealth into public assets, through the institutions (without corrupt officials or

magistrates) and the law. Therefore civil economy, the civitas is fundamental.

This is Vico and di Galiani’s a coherent theory of the heterogenesis of the objectives. We

find, however in these writers, a particular accent which is common to the Italian tradition of civil

economy: private interests do not always naturally become public virtues; it occurs only in civic

life, only within those institutions and laws that regulate civic life. (Nuccio 1995). The savage men

“the lone giants” (Vico) do not know of this spontaneous order, which is assured only by civil life.

The key-words of Genovesi

• Market– Reciprocal help (reciprocity even in the economic market).

• Public trust – The first natural resource of a region is trust.

According to Genovese, wherever trust occurs, the market also occurs. For the English

thinkers, the market arrived first, and trust, fidelity and fairness came afterwards. In this way trust

became an economic resource.

Culture must therefore be popular, and not like Latin, accessible only to certain social

categories. It must be available to everyone, so what is necessary is civil economics social

capital.

• Public trust – Economics = Happiness

Filangieri led the first Neapolitan school (1750-1799), influenced by Aristotlian thought: one

cannot be happy in isolation. One can be rich in isolation, but to be happy requires at least two

persons.

Public happiness. Public because it was still the business of the sovereign. However it

presses for the ideal conditions for welfare and social security, the reason whereby in Naples this

period coincided with the reign of Charles IV of Bourbon.

The civil economy tradition of happiness is public because it is linked to the common good,

which is the goal of government activity, of the “science of administration”, and must therefore

become the ideal of the good governance of the sovereign, “who is the supreme and independent

moderator of public happiness, - the happiness of the entire body and foe each limb”.

• Social capital – there are three perspectives:

- The course of development until the 1950s, which extended up until the 60s/’70s,

emphasised physical capital (machines, premises, technology). Development is

fostered by investing in technology and machinery.

- The economic development of a country cannot rely on good machinery alone;

human resources are also necessary, especially properly trained human resources.

Physical capital must be accompanied by human capital.

- The presence of human capital does not however automatically mean

development. It is also necessary to be able to build relations with others. The

need that emerges, therefore, is the knowledge of how to create relationships with

others.

Public trust is lacking.

Genovese stated that there was a lack of public trust, and this would explain why Naples has

not developed in a big way as Milan has done. There is a lack of reciprocity, of trust.

The society organised on the basis of public trust requires genuine and earnest conduct; as

relationships become more complicated, the affairs of the market become simpler. Customers never

demand reciprocity from the market (an intrinsic relationship). In fact this is to do with the theme of

social economy – the focus is not on profit, but on social relations.

5. The fragility of relational goods

The return of happiness as a theme in economics is due to the emergence of a new fact.

Economists themselves has always known that wealth alone does not bring happiness. The often

implicit hypothesis underlying economic analysis was that even if wealth or economic well-being

did not always bring a “proportional” increase in happiness, it did not would not however entail its

diminution.

For this reason, especially in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, economics has confined its concern

to a sphere much less complicated than happiness: wealth or (economic) well-being – while

realising of course, that much of peoples’ happiness depends on non-economic factors such as

relationships and emotions, which have nothing to do with the market.

Recently, however, a new fact has emerged: in the high income society, having a greater

income does not make us more happy, or at least makes us less happy than we would expect. This

observation has prompted economists during the last 25 years to study happiness more thoroughly

(the pioneering work was by Easterlin, 1974), and today many “believe that happiness should once

more occupy a more central place in economic science” (Dixon 1997, p. 1812).

The debate carries on, and there is much disagreement on non-secondary points. Easterlin

(2000) for example holds that “the relation between happiness and income is very complex. In a

given moment in time, those who have more money are on average, more happy than those who

have less. If however we consider the cycle of life as a whole, the average happiness level of a

group remains constant despite a considerable increase in income.” (p. 1). Synchronic analyses of

data from various countries demonstrate a positive and significant correlation between happiness

and income, while diachronic analyses performed on the same groups of people show that in the

course of time happiness remains very nearly constant and is not dependent on variation in income.

But the mere revelation of the paradox is not enough for economists: they want to explain it,

to discover the reason why the relationship between income and happiness should progress so

differently to the way that common sense would suggest, and differently to what social scientists

have always hypothesised.

There are many explanations, but one idea runs through all the different theories: in

concentrating on its variable focal points, (income, wealth, consumption…) economic science

neglects something more important which reflects on people’s happiness or well-being.

While it is true that economists have only recently begun to look at happiness, psychologists

have on the other hand been analysing it for fifty years with the result that the study of happiness is

now a very fertile field of interdisciplinary research.

In 1971, two psychologists carried out a study on the relations between income and

happiness of certain subjects; by way of example, one outcome of the research suggested that

winning the lottery left people less happy than before.

There are at least three theories in the field of psychology that seek to explain the relationship

between wealth and happiness. They are described thus: (a) Comparative perspective, (b) Goal

attainment and (c) Hedonic approach. Proponents of the comparative perspective argue that

happiness derives from the comparison of one’s own economic position and that of a reference

group. The, goal attainment perspective regards wealth as a potential source of well-being because

it places people in conditions where they can fulfil the objectives that come before them. Finally,

the hedonic perspective considers wealth as a means that permits the individual to live in a more

satisfying way.

Richard Easterlin made a study in 1974 on the daily life of Americans– family, work,

friends, leisure, etc.

oldickeastman@q.com