AT&T's forgotten plot to hijack the US airwaves

Matthew Lasar

Oh, sorry—before we get too far into this exclusive, we should probably add that the scheme was hatched in 1922 and abandoned by 1926. But if it's not a breaking story, it's still relevant history. Right now the Federal Communications Commission is proposing a massive transfer of broadcast spectrum to the wireless industry, whose principals, AT&T included, are providing all of the services offered by television and radio broadcasters—with voice and Internet too.

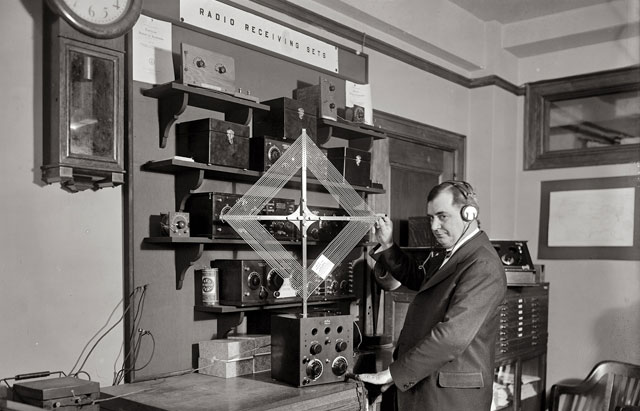

This is all new to us because we take for granted the old over-the-air broadcast licensing system that we've lived with for almost a century. But nothing was old at the dawn of broadcast radio in the early 1920s. Let's go back to those days and explore an alternate history that never happened—until now.

Fictionalists

It was August 28, 1922, and radio station WEAF in New York City was airing a ten-minute talk by a representative of a real estate company praising the virtues of fine literature and suburban living. "It is fifty-eight years since Nathaniel Hawthorne, the greatest of American fictionalists, passed away," the executive began. "To honor his memory, the Queensboro Corporation, creator and operator of the tenant-owned system of apartment homes at Jackson Heights, New York City, has named the latest group of high-grade dwellings 'Hawthorne Court'."

Many historians identify this highbrow little speech as the first radio commercial. The station charged $50 for it, and another in the evening for $100. But what is less often highlighted is that the frequency in question was owned by AT&T, which, true to its telco spirit, didn't call the ad an ad, but a "toll-cast" presentation.

If Ma Bell wanted to get into broadcasting, so did everybody else, including hotels, restaurants, schools, community centers, Pentacostalist preachers, quack doctors, and electrical appliance factories. And why not? There were no hard and fast rules yet about who could start a radio station, or what they could do with it. But AT&T was in a particularly good position to dominate this field, because it had played a crucial role in the creation of the telecom sector after the First World War.

While millions of Americans were marching Over There, the United States Navy had taken over the nation's telecommunications system over here—telephone, telegraph, and cable. Not surprisingly, Navycrats wanted to keep control over wireless after the peace. But government administration of railroad and telecom services had been terrible for consumers—driving up communications and transport prices. That and massive censorship of the press during the war shut down any public support for this experiment. So in 1919 Navy officials opted for their next best choice—driving out of town their rival for dominance over the airwaves, the hated Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. The administration of Woodrow Wilson petitioned General Electric not to sell Marconi the crucial new state-of-the-art alternators that would pave the way for broadcast radio in the 1920s.

Seeing the writing on the telegraph tape, British Marconi divested itself of its American holdings, and G.E. Vice President Owen Young became Chair of the Board of a new company: the Radio Corporation of America. RCA's mission was "to link the countries of the world in exchanging commercial messages," declared its founding press release. But RCA soon discovered that it had a rival. Not only was AT&T slowly expanding its control over the nation's telephone lines, but it owned key vacuum tube patent rights crucial to wireless reception.

So in July of 1920, RCA and AT&T cut a deal. The former would control ship-to-shore and oceanic telegraphy. The latter would hold rights to land-based wireless and exclusive rights to "all land radio telephony for toll purposes." AT&T also owned RCA stock and had representation on the company's board of directors. But while these executives were hashing out the details that summer, they still thought the future was about wireless Morse code. Four months later, however, a station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania named KDKA began voice and music transmission over the airwaves. As the mania for "radio" spread across the country, both companies realized that they each held keys crucial to the nation's media future.

The quickest way

All this maneuvering took place when nothing was in cement, broadcasting-wise. As radio historian Susan Smulyan has noted, when KDKA went live in 1920, nobody knew how to make money from this new technology. In fact, one magazine held a contest for the best essay on how to"monetize" radio, as we would say in contemporary jargon. It might amuse Ars readers to learn that pretty much everybody agreed that commercials represented the worst possible option. "The quickest way to kill broadcasting would be to use it for direct advertising," warned then Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover. "If a speech by the President is to be used as the meat in a sandwich of two patent medicine advertisements there will be no radio left." RCA Vice President David Sarnoff agreed. Soon he would propose a "super power" system in which a few high powered transmitters would broadcast radio fare to the whole country, the content subsidized by the sales on radio receivers.

But AT&T had another idea—a network of almost 40 radio stations strung together via the telco's long distance lines. They would broadcast to local areas wirelessly and share content via AT&T's long routes. The company intended WEAF as the beginning of that experiment. In 1923 it broadcast the annual meeting of the National Electrical Light Association via its copper wires across AT&T stations in New York, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Schenectady. The telco also hoped to transmit a speech by President Warren Harding from San Francisco, but bad luck nixed the plan. "The cancellation of the speech because of Harding's illness and subsequent death deprived AT&T of a broadcast audience estimated at between three and five million people," Smulyan writes.

Undaunted, the carrier networked a speech to Congress by Harding's successor, Calvin Coolidge. Meanwhile its executives held internal meetings hatching grand plans. On February 16, 1923, the corporation launched a lengthy all Bell System conference to come up with a viable vision for consolidating its hold over radio. Broadcasting historian Steve Wurtzler summarizes what they envisioned as follows:

AT&T proposed developing U.S. radio as a dispersed, largely decentralized array of noncompetitive local broadcast stations operating at transmission power levels designed to reach members within a specific community. AT&T would construct, own, and operate a single broadcasting station in virtually any town of consequence in the United States. Within this model, programming would be predominantly local in origination, with the community itself determining the content, standards, and nature of broadcast material. Programming policies and decisions were to be vested entirely in the hands of a local broadcasting association consisting of community leaders and the general public. When the local broadcast association wished it, AT&T would provide through a modified version of their long-distance telephone system interconnections between local stations for programming of abiding national or regional interest.

As for competing stations, they would be "minimized or foreclosed through the efforts of the local broadcast associations to function inclusively," Wurtzler explains, "encouraging all... to join in the shared collective effort."

If this sounds all nice and Woodstocky in print, AT&T's implementation of the concept was far less pretty in practice, and that led to the scheme's demise. First the telco began denying non-Bell System radio stations access to its long distance lines for shared projects, forcing other networks to experiment with inferior telegraph rather than telephone connections for their experiments. Then AT&T drew more anger by suing a nearby competitor to WEAF, claiming that its broadcast operation infringed on the carrier's patents. "To the public, already disturbed at the growth and power of trusts and cartels, AT&T seemed to be jumping with hobnailed boots over the little fellow," write historians Christopher Sterling and John Kitross.

Soon Ma Bell executives were starting to reconsider this grand plan. It was generating bad press, they worried, and getting in the way of the Holy Grail—convincing state utilities commissions to allow the corporation to gradually absorb all the nation's profitable independent phone companies, a fait accompli by the late 1930s. By 1926, "not only had AT&T wearied of the battle," Sterling and Kitross conclude, "but such a competitive business did not fit its longstanding corporate philosophy. This philosophy favored monopoly, such as it had in long-distance telephony, over head-to-head competition."

The toll road not taken

And so AT&T swallowed its pride and settled with RCA, agreeing to drop its grand broadcasting plans in exchange for a profitable monopoly on providing wireline connections between radio stations. RCA's Sarnoff, however, quickly discovered that the public was just as suspicious of his "super power" scheme as it had been of AT&T's broadcast radio dreams. And so another compromise was reached. In 1926 RCA, G.E., and Westinghouse launched the National Broadcasting Company. NBC offered syndicated programming to independent stations via AT&T hookups, complete with the advertising that Hoover had claimed would kill the medium. Not until four decades later would the nation create a system of public broadcasting to compete with NBC and its parallel networks: CBS and ABC.

What are we to make of this short-lived technological gambit? It would be easy to celebrate AT&T's demise in this area, and counterfactual history is always a tricky game. But it seems to us that an opportunity was lost here. The Bell System's withdrawal from broadcasting left both radio and television in the hands of one technological institution, the licensed broadcast station. The owners of these entities quickly morphed into a powerful political lobby, constantly standing in the way of competing platforms, such as cable television, satellite radio, Low Power FM, and white space broadband.

And had AT&T stuck to its guns and tried to stay in the broadcast content game (albeit with more diplomacy and kindness), the company might have brought some of the innovations to broadcasting that we're only starting to enjoy today with the iPhone, BlackBerry, and Droid. The carrier might have also seen the potential for the Internet far sooner than it eventually did.

In the end, this story is analog water long gone under the digital bridge. We'll never know what might have happened otherwise. But one thing is clear—our over-the-air broadcasters never came to their dominance in American media via some inevitable or inherently logical process. Happenstance and good luck brought them this windfall. Whether their luck was also our's remains an open and ongoing question.

Further reading

- Susan Douglas, Inventing American Broadcasting

- Hilliard and Keith, The Broadcast Century and Beyond

- Susan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting

- Sterling and Kitross, Stay Tuned: A Concise History of American Broadcasting

- Steven Wurtzler, "AT&T Invents Public Access Broadcasting in 1923," in Communities of the Air, Radio Century, Radio Culture

Written April 2010

FW: 1/24/11

arstechnica.com/telecom/news/2010/04/atts-forgotten-plot-to-hijack-the-us-airwaves.ars